Digitizing the Past

I subscribe to what is called Internet Archive (archive.org). The Internet Archive, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, is building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form. Like a paper library, they provide free access to researchers, historians, scholars, people with print disabilities, and the general public. Their mission is to provide Universal Access to All Knowledge. They boast a growing library of 735 billion webpages, 41 million books and texts, 14.7 million audio recordings, 8.4 million videos, 4.4. million images and 890,000 software programs. It is an amazing resource for older, out-of-date, archival works and records.

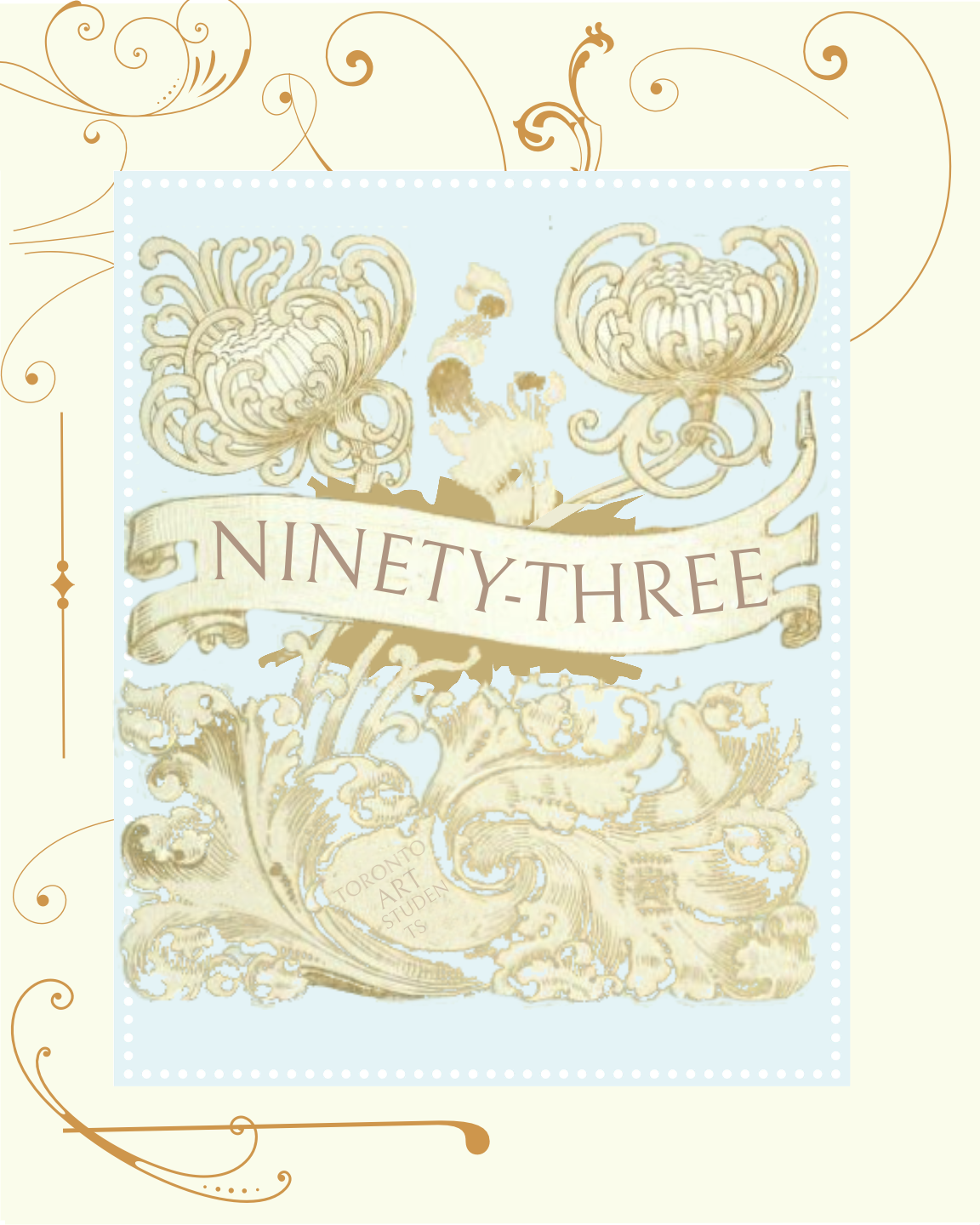

Recently, they posted old turn-of-the-century calendars as we enter 2023 ourselves. I took two of the public domain calendars, one published in 1893 and the other in 1901, and sought to digitize them, not just take a picture of it and post it, like the Archive does, but rather recreate them using modern digital means. I am no expert at this, but I did the best to retain the overall sense of the artwork and texting. I used a combination of Adobe InDesign, Adobe Photoshop, and Tobias Saul's Kittl (kittl.com) for the work. The faded patterns remain and the work took several days of playing around with settings and cut-and-paste and tweaking the color schemes and so forth. The results are below.

Enjoy the remade 1893 and 1901 calendar covers!

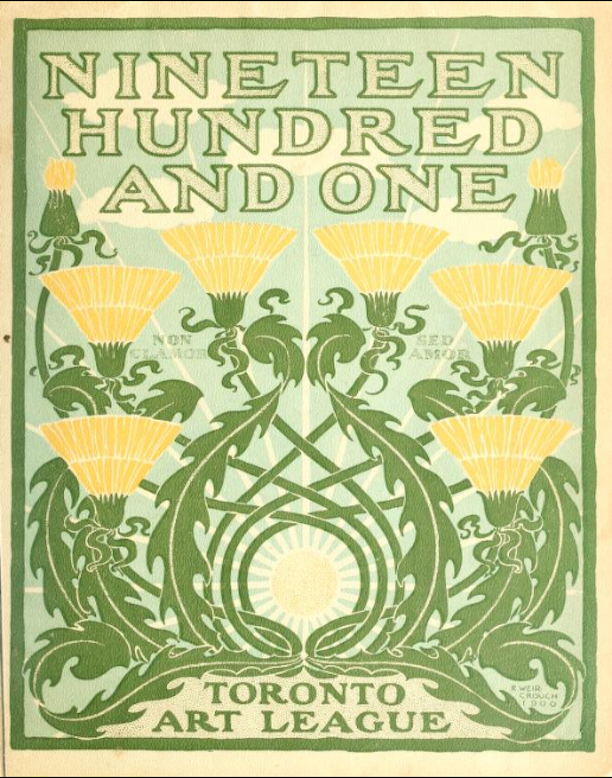

ORIGINAL 1901 CALENDAR COVER

Calendar for the year 1901 (Toronto art league)

by Toronto art league

Publication date: 189?

Publisher: Toronto Art Students League, Musson Book Co

Collection: Queens University Toronto

Digitizing sponsor: Ontario Council of University Libraries & Member Libraries

With verses by some of the Canadian writers of verse, and drawings by members of the Toronto art students' league

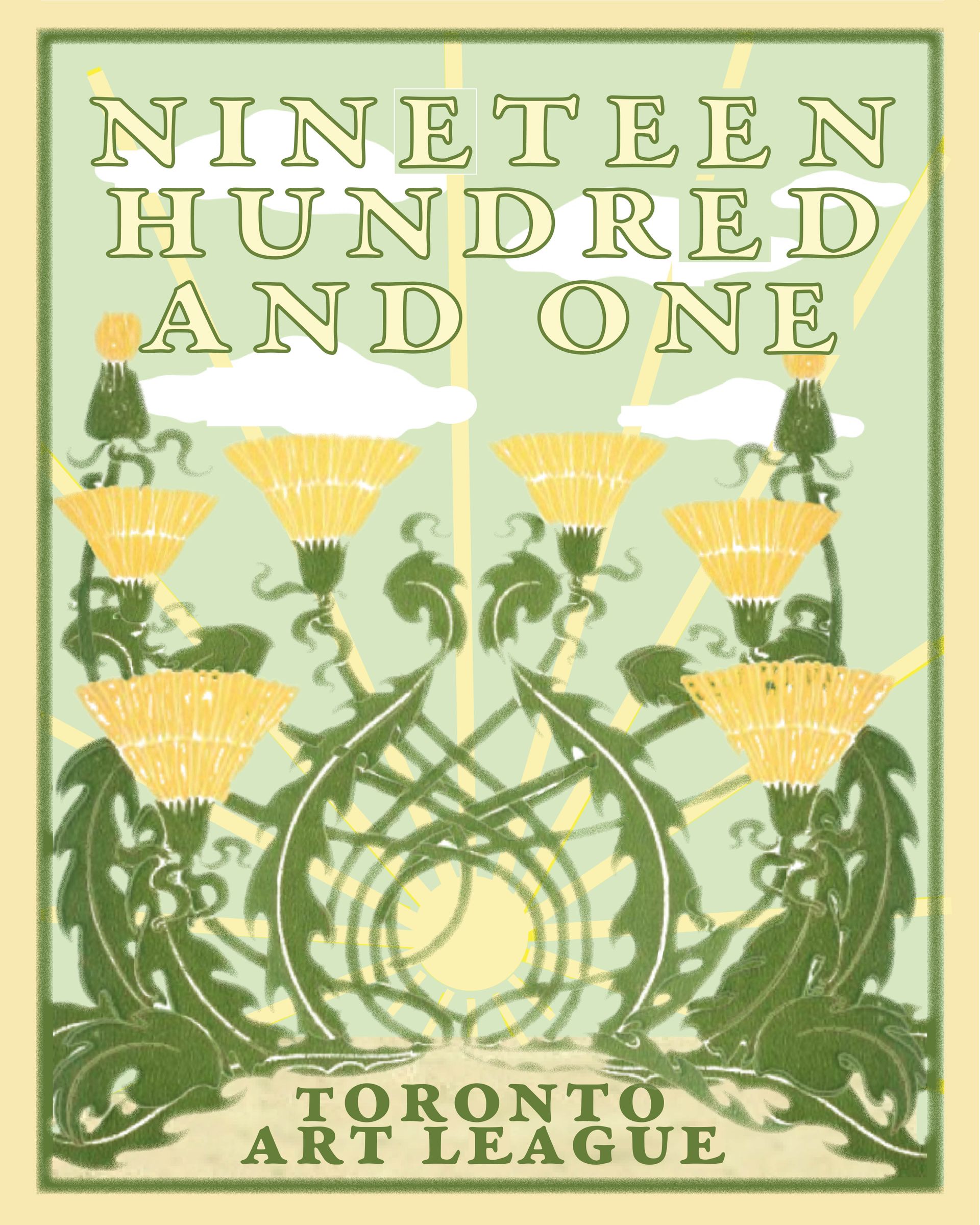

This is the redone digitized cover. While not exactly the same as the 1901 edition, I tried to stay true to the overall colors and fanciful artwork.

The lettering was especially challenging. I used Garamond Premier Pro, Bold Caption for the text. I used the "create outline" function of InDesign on the text to then enhance the capital "E" lower serif to match the original drawing text.

The background art work was done in the very excellent graphics program provided by Kittl and tweaked in InDesign. The background color was matched to the original, with clouds added and then sun with rays that had to be drawn individually and rotated in place. It is certainly clearer than in the original and I could have tweaked it more to make it fade more into the background.

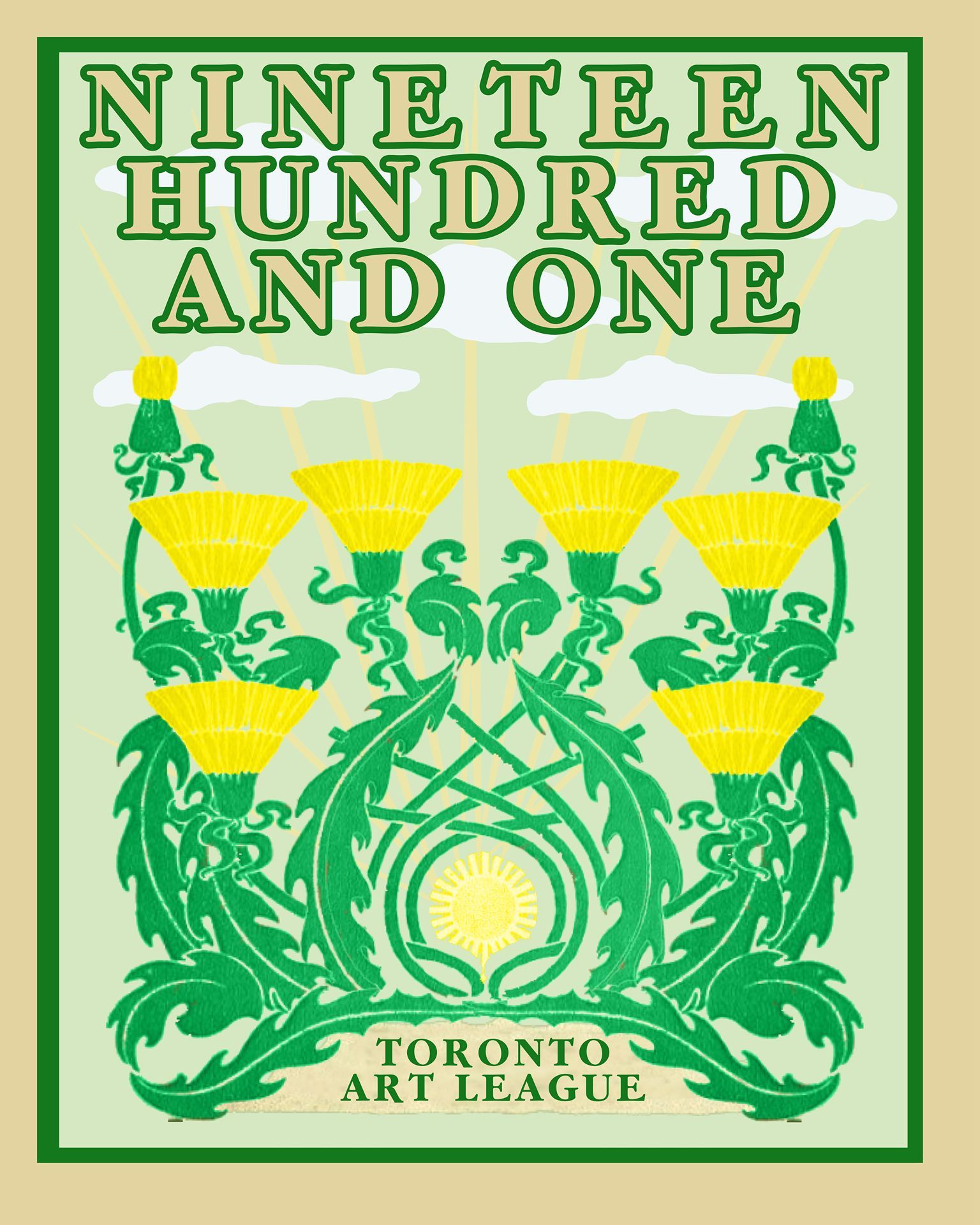

This is the newly redone 1901 Calendar front. The vines and flowers were copied and newly colored in Photoshop. The rest of the artwork was done in Kittl with the import of the revised Adobe Garamond Bold from Fontographer for the elongated "R" and "E."

Note the clarity and sharpness of the newly minted image.

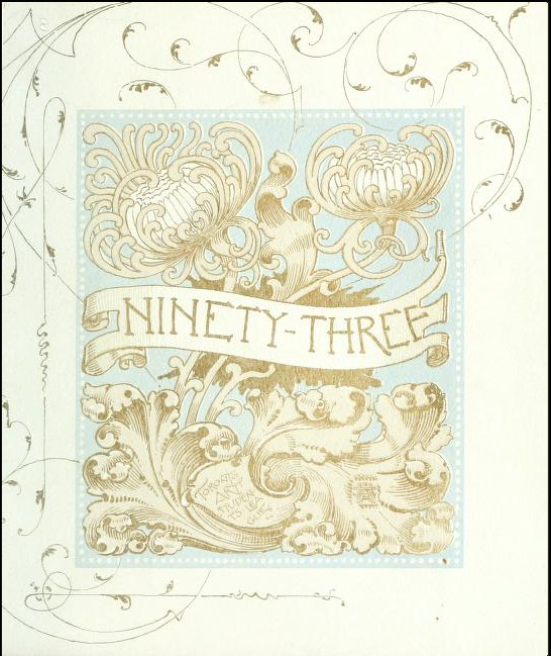

Ninety-three: a calendar for the year of our Lord MDCCCXCIlI; with verses by some of the Canadian writers of verse and drawings by members of the Toronto Art Students' League

By: Toronto Art Students' League

Published: 1893

Collections: Dorothy H. Hoover Library - Ontario College of Art & Design

The publication contains the latin moto: "Non clamor sed amor" which translates as "Not clamour, but love" which is a line by Tommaso da Celano (13th century)

Courtesy: Internet Archive

This is the digitized 1893 Calendar. I used Photoshop to capture the interior artwork and coloring, and Kittl to print out the distorted "ninety-three" and add the Victorian flourishes. Text is Bellefair Regular. Note the flourishes are not exactly like the original.

Successful Layout & Design