Blog

More on the Greek font. In a previous post ( It's Greek To Me! March 18, 2023) we noted that Cursive Greek type appeared as a chancery script by Francesco Griffo in 1502 and lasted two hundred years. Robert Bringhurst notes that "chancery Greeks were cut by many artists from Garamond to Cason, but Neoclassical and Romantic designers . . . all returned to simpler cursive forms . . . in the English speaking world the cursive Greek most often seen is the one designed in 1806 by Richard Porson." This face has been the "standard Greek face for the Oxford Classical Texts for over a century." ( Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style, Hartley & Marks, Version 3.1, 2005 , pp. 274, 278) In fact, asking Google for the best Greek face to use, it points us to Porson Greek. Porson is a beautiful Unicode Font for Greek. It's not stiff, like many of the cleaner fonts, which are usually san serif. It is bold and easy to read and seems to more closely match the orthography in newer textbooks. (Jan 8, 2004)

Historical Literary Fonts: The Fell Fonts Rooted in John Fell's legacy at Oxford, these fonts inherit a rich history of learned printing, drawing inspiration from Dutch typefaces with contrasting weights and unique letterforms. The Fell type collection was a gift made to Oxford University by Dr. John Fell (1625–1686), Bishop of Oxford and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford. They were donated to the Oxford University Press (OUP) and became the foundation of its early printing identity — “He bought punches and matrices in Holland and Germany in 1670 and 1672 and entrusted his personal punchcutter, Peter de Walpergen, with the cut of the larger bodies. Igino Marini, revived some Fell types in 2004.”[1] Why the Fell Types Matter Fell Types represent pre-Caslon English typography. They form one of the earliest consistent typographic identities of a university press. They show how Dutch type design influenced English printing. Typographically, they were designed for reading, not display. This is important because they departed from the socialistic, anti-industrialization movement of the Arts & Crafts movement led by William Morris (SEE Blog Advances in Typography: A Historical Sketch (Part 2) , Nov. 20, 2025). Much credit for the original fonts goes to Frederick Nelson Phillips and his work at The Arden Press, which became more commercially ambitious and influential. This press produced high-quality editions of classic and scholarly texts, collaborated with academics, editors, and publishers and continued refinement of typographic discipline. Frederick Nelson Phillips Frederick Nelson Phillips (c. 1875 – 1938) occupies a crucial transitional role between Arts and Crafts idealism and twentieth-century typographic rationalism, as well as between private press craftsmanship and professional publishing. For historians of printing, he represents a model of how tradition can be revived thoughtfully—without nostalgia, and without surrendering to industrial mediocrity. Frederick Nelson Phillips was a British printer and typographic entrepreneur best known as the founder of The Florence Press and later The Arden Press. He played a significant role in the early twentieth-century revival of fine printing in Britain, working in the wake of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, yet moving toward a more practical, commercially viable model of quality book production. Although never as famous as Morris or later modernist typographers, Phillips exerted a quiet but lasting influence. He helped normalize the use of historical typefaces in serious publishing, bridging the gap between private press ideals and commercial book production. Phillips influenced later British typographic standards, particularly in academic publishing. He contributed to the preservation and renewed appreciation of early English type design. His work resonates strongly with later figures interested in typographic scholarship, including those associated with university presses and fine publishing.

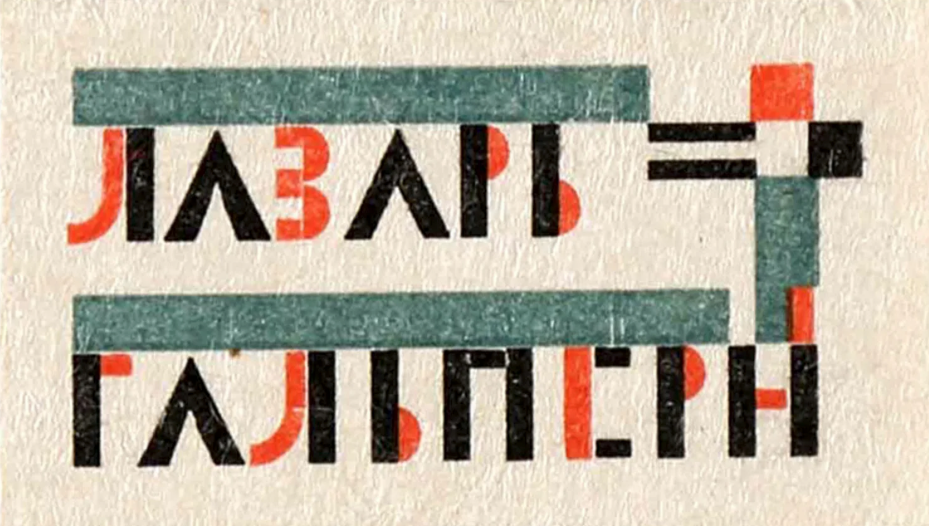

Nothing New Under The Sun: A Look at Current Typographic Trends As a typographic historian of sorts, and owner of CARE Typography, a small design studio focusing on reviving historic and often missed typefaces, I read a number of type reports and books. Of special interest is the newsletter from the Monotype corporation highlighting trends and faces for today. (See https://bit.ly/3Y1R1BV ) A couple of statements in their latest reports by Phil Garnham, Creative Type Director, at Monotype got me thinking about culturally laced typographic styles and faces that have graced our historic type landscapes. He notes a “new universal style emerging: flat design in modern online brands, almost reverting to the minimalist style of five years past. Many companies are going for clean geometric style with type.” This is hardly a new concept or trend. A deeper dive into the history of type design over the centuries helps us understand what may be happening. In the history of typography, on which I have written (See H. Carl Shank, Typographical Beauty Through the Ages: A Christian Perspective, Lulu.com, 2025), the visual dissonance of the Dadaist movement in type was replaced by the order of Constructivism and its functional accessible design principles. Art Deco gave way to Swiss type beauty with its readability and visual harmony in the faces of Helvetica and Univers. Grunge and Psychedelic type by Wes Wilson gave way to the sans serifs used universally today. Hippie children of the 60s grew up to be corporate CEOs of the 80s and 90s, shedding their anti-establishment and even destructive behaviors for the boardroom and nice houses with ordered yards and gardens. This has been the story of all cultural movements, including typographic movements. They reflected their cultural morés of the times, but the bold, audacious, violent, raucous types always gave way to what we internally want and desire — a return to simplicity, functionality and order and type viability. From a theological viewpoint, the thought provoking words of the writer of Ecclesiastes of the Bible apply here — “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun. Is there a thing of which it is said, “See, this is new”? It has been already in the ages before us.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9, 10) “Customers are seeking affinity with brands that seek justice in our world, and that goes beyond a brand’s mission. People want to see brands actively involved in solving societal problems.” The issues of climate change, diversity movements, equity and inclusion initiatives are seemingly new but typographically rehearse type’s movements from Gutenberg to today. Calligraphers and typographers have been dealing with cultural changes and shifts for ages. I applaud what Monotype and others are seeking to do with variable fonts and digital type, but I would historically caution us in the business not to place too much excitement and hubris after cultural trends. Carl Shank CARE Typography December 2025

AI & Typography: A Christian-Theistic Present Look Monotype Corporation recently released their 2025 Report concerning Artificial Intelligence and Typography called Re-Vision (See https://bit.ly/4aEUePf ). This eReport looks at the various typographical, social and cultural issues surrounding AI and how it affects and impacts the craft and science of typography. A selected summary of the Report is available below.

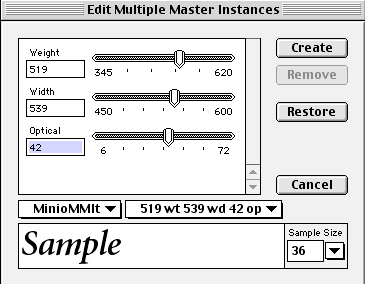

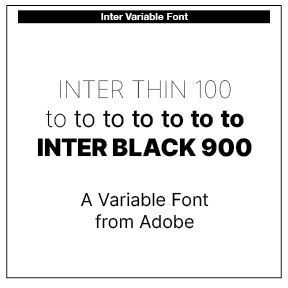

Variable Fonts: An Introduction History & Use “Variable fonts are a single font file that behaves like multiple fonts.” (John Hudson) The technology behind variable fonts has been around for a while. Starting in the 1990s, interpolation and extrapolation have been used to create different masters, and weights in typefaces. For example, by designing a regular and bold weight a semibold could be interpolated from the two masters.

Advances in Typography: Late Twentieth to Twenty-First Centuries A Historical Sketch (Part 3) Late Twentieth to Early Twenty-First Century: Corporate and Contemporary Digital Jonathan Hoefler (b. 1970) is an American type designer known for influential typefaces such as Hoefler Text, Gotham, Knockout, and Mercury. Gotham, co-designed with Tobias Frere-Jones, gained international fame through its use in Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign and has since become a staple in corporate and editorial branding. Born in New York City, Hoefler’s early fascination with everyday typography led him to a self-taught career in type design. In 1989, he founded the Hoefler Type Foundry, quickly earning recognition with Champion Gothic for Sports Illustrated. His partnership with Roger Black and later Tobias Frere-Jones resulted in dozens of widely used typefaces. Hoefler’s work is characterized by a blend of historical research and modern engineering, shaping digital typography standards. His typefaces are used by major publications, cultural institutions, and corporations worldwide. In 2021, Monotype acquired his company, marking a significant moment in the evolution of digital type design. Hoefler’s approach has redefined contemporary type design, bridging historical revivals and modern usability. His influence extends across print and digital media, setting new standards for clarity, versatility, and typographic excellence.

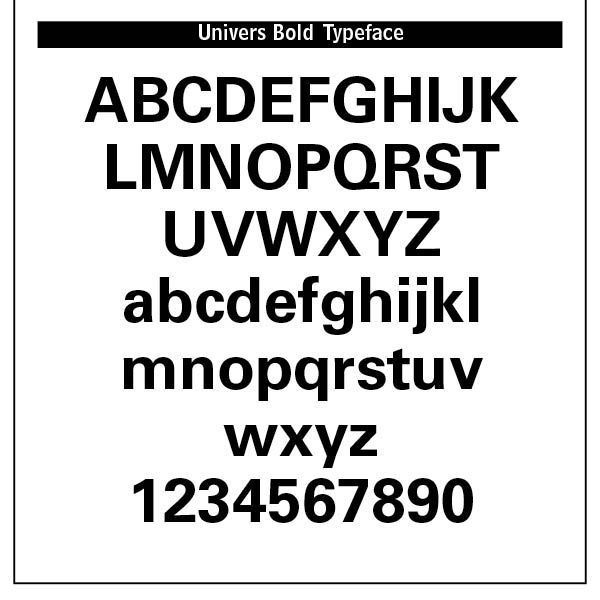

Mid-Century Modernism & Corporate Typography (1945–1980) Designers like Jan Tschichold were foundational to many of the Swiss design principles. This style evolved from Constructivist, De Stijl and Bauhaus design principles, particularly the ideas of grid systems, sans-serif type and minimalism. Emerging in Switzerland during the 1940s and 1950s, this typography, also known as the International Typographic Style, directly responded to the type chaos of Dada and the stylization of Art Deco. The International Typographic Style (or the Swiss Style) in the 1950s and 1960s focused on grid systems, objective communication and sans-serifs. Key figures were Josef Muller-Brockmann, Emil Ruder and Armin Hofmann. The Swiss style emphasized readability, visual harmony and universality. Clarity, objectivity and functionality were key components. Contributors included Max Miedinger, creator of the Helvetica typeface (1957 by Miedinger & Eduard Hoffmann), and Adrian Frutiger, creator of the Univers typeface in 1957, and Hermann Zapf, creator of Optima in 1958. Swiss style became the dominant graphic language of postwar corporate identity. Other Blogs I have written noted the development of Helvetica ( “Helvetica’s Journey” July 13, 2024 ). Adrian Frutiger (1928–2015) was a Swiss typeface designer whose career spanned hot metal, phototypesetting and digital typesetting eras. Frutiger’s most famous designs, Univers, Frutiger and Avenir, are landmark sans-serif families spanning the three main genres of sans-serif typefaces —neogrotesque, humanist and geometric. Univers is a clear, objective form suitable for typesetting of longer texts in the sans-serif style. Starting from old sketches from his student days at the School for the Applied Arts in Zurich, he created the Univers type family. Folded into the Linotype collection in the 1980s, Univers has been updated to Univers Next, available with 59 weights. This lasting legible font is suitable for almost any typographic need. It combines well with Old Style fonts like Janson, Meridien, and Sabon, Slab Serif fonts like Egyptienne F, Script and Brush fonts like Brush Script, Blackletter fonts like Duc De Berry, Grace, San Marco and even some fun fonts. Univers is not a “free” font and must be purchased from Linotype. Other faces by Frutiger are Frutiger and Avenir. These fonts were designed to be legible, versatile and anonymous, avoiding stylistic “noise” to focus on clear communication. Swiss type used a systematized approach to typography, enabling consistent spacing, alignment and hierarchy, crucial for multilingual and complex layouts. Typography was seen as part of a harmonious, modern composition. Generous white space facilitated clarity and focus.

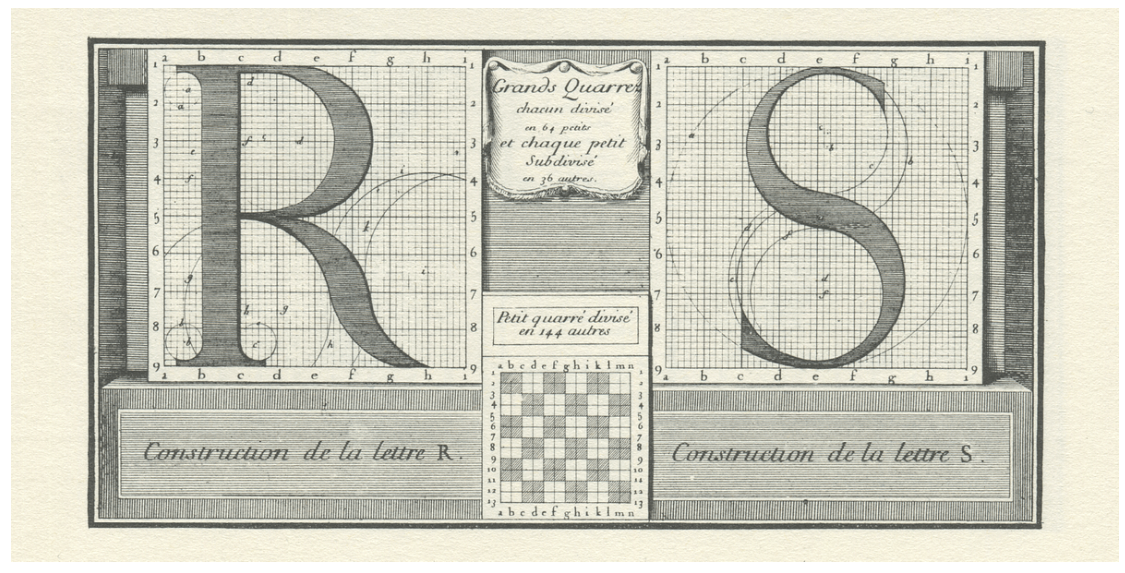

Advances in Typography: Twentieth Century A Historical Sketch (Part 1 ) Early Twentieth Century: Form Follows Function Bauhaus Precursor The Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Foundation, est. 1907, Munich) was a pivotal German association of artists, architects, designers, and industrialists that advanced rational, industrial design and laid the foundation for modernist sans-serifs. The Werkbund emphasized functionalism, simplicity, honest use of materials, and alignment with industrial production, rejecting unnecessary ornamentation and anticipating the principle “form follows function.” Its purpose was to elevate German industrial products by integrating artistic excellence, technical innovation, and industrial manufacturing, summarized by the motto: “From work to form”—good design as a cultural and economic asset. Key founders included Hermann Muthesius, Peter Behrens, Fritz Schumacher, and Karl Schmidt. Their goals were to enhance everyday objects through quality design, foster a unified visual culture in Germany, partner artists with industrial manufacturers, promote standardization and modern production techniques, and compete internationally in design excellence. The Werkbund is recognized as a precursor to the Bauhaus and modern industrial design. Notable members included Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Peter Behrens. The organization established principles of functional, simplified forms, standardized mass production, and the concept of design as a cultural force. They hosted influential exhibitions, notably the 1914 Cologne Exhibition, as well as publishing journals and defining standards for high-quality design. Futura & Geometric Modernism (1920s–1930s) As we saw in my last post, between 1500 and 1900 typography evolved from Renaissance humanist forms to industrial mass production and artistic revival. Old style typefaces (like Garamond) moved to Transitional faces (like Baskerville) to Modern/Didone faces (like Didot and Bodoni) to Industrial display types (fat faces, slab serifs, sans serifs) to the Arts & Crafts revivals. Art Nouveau was a reaction against the academicism, eclecticism and historicism of nineteenth century architecture and decorative art. The new art movement had its roots in Britain, in the floral designs of William Morris, and in the Arts and Crafts movement founded by the pupils of Morris.

Industrial Revolution and Display Typography (1800–1870) I have recently viewed the broadcasts of Great Canal Journeys, a narrated insight into Britain’s canals and waterways by two married and retired actors. They have been responsible for the restoration of a number of Britain’s canal systems. They noted that the Industrial Revolution in that country brought about the almost demise of the canals for moving products across the continent. The railroads took over much of the movement of goods from one place to another. In much the same way, typography and printing were forever transformed by the Industrial Revolution. Britannica notes that “the Industrial Revolution changed the course of printing and typography not only by mechanizing a handicraft but also by greatly increasing the market for its wares. Inventors in the nineteenth century, in order to produce enough reading matter for a constantly growing and ever more literate population, had to solve a series of problems in paper production, composition, printing, and binding.”