Font Master: Frederick W. Goudy

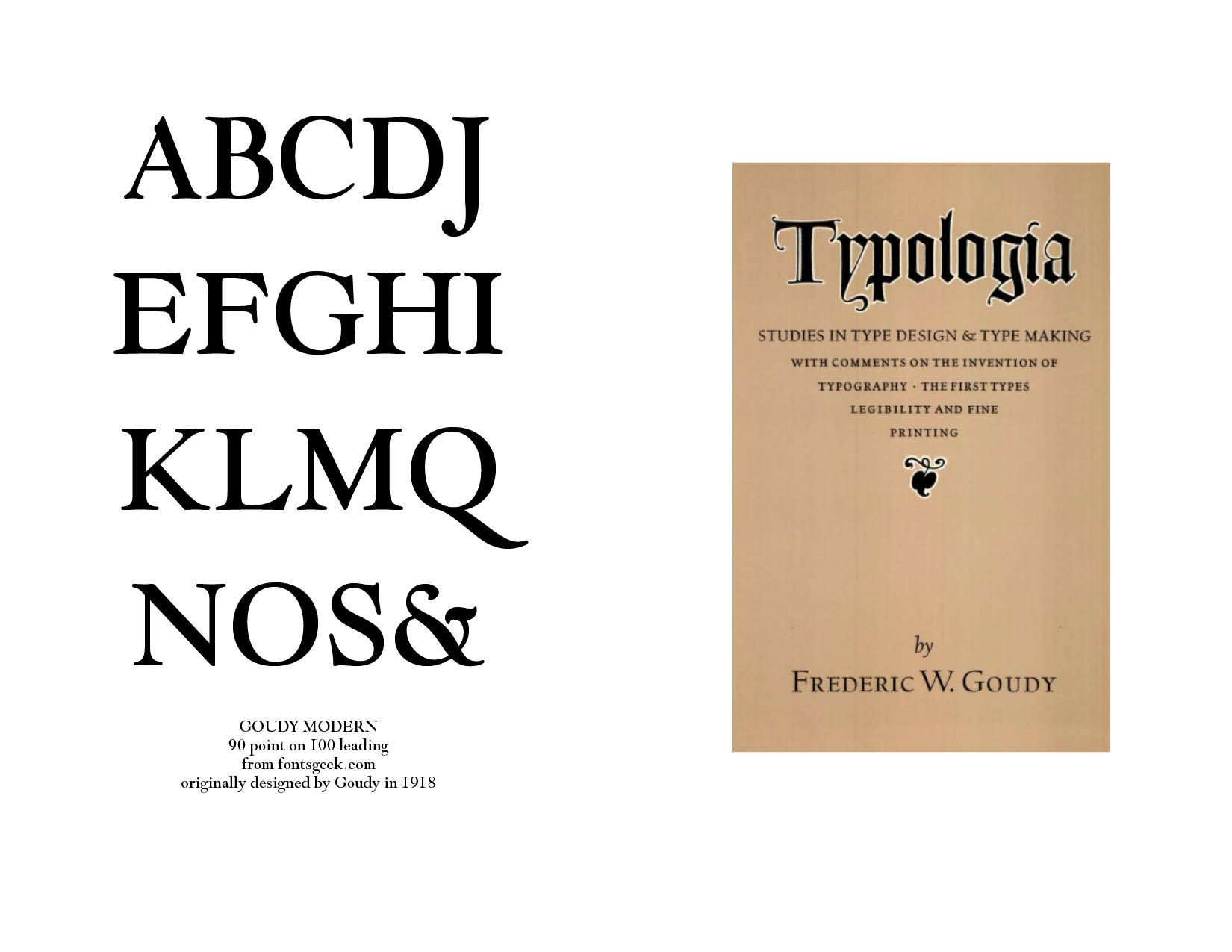

Font Master — Frederick W. Goudy. There is perhaps no other more celebrated font creator than Frederick Goudy, certainly not in the first half of the twentieth century. Goudy provided the type and printing world with a both legible and beautiful typeface. In his master work, Typologia: Studies in Type Design & Type Making, With Comments on the Invention of Typography • The First Types Legibility and Fine Printing (University of California Press, 1940, 1977 Reprint), Goudy says that more than legibility is important — "but this is not enough, for types should be pleasantly readable too, a quality depending somewhat on the ability of the arranger of the letters, as well as partly inherent in the letters themselves." (129–130) He notes that "the proper standard of beauty in types resides, first of all, in their utility, but I believe also that there are secondary esthetic attributes which may be included in their design with no sacrifice of life and vigor and legibility." (77)

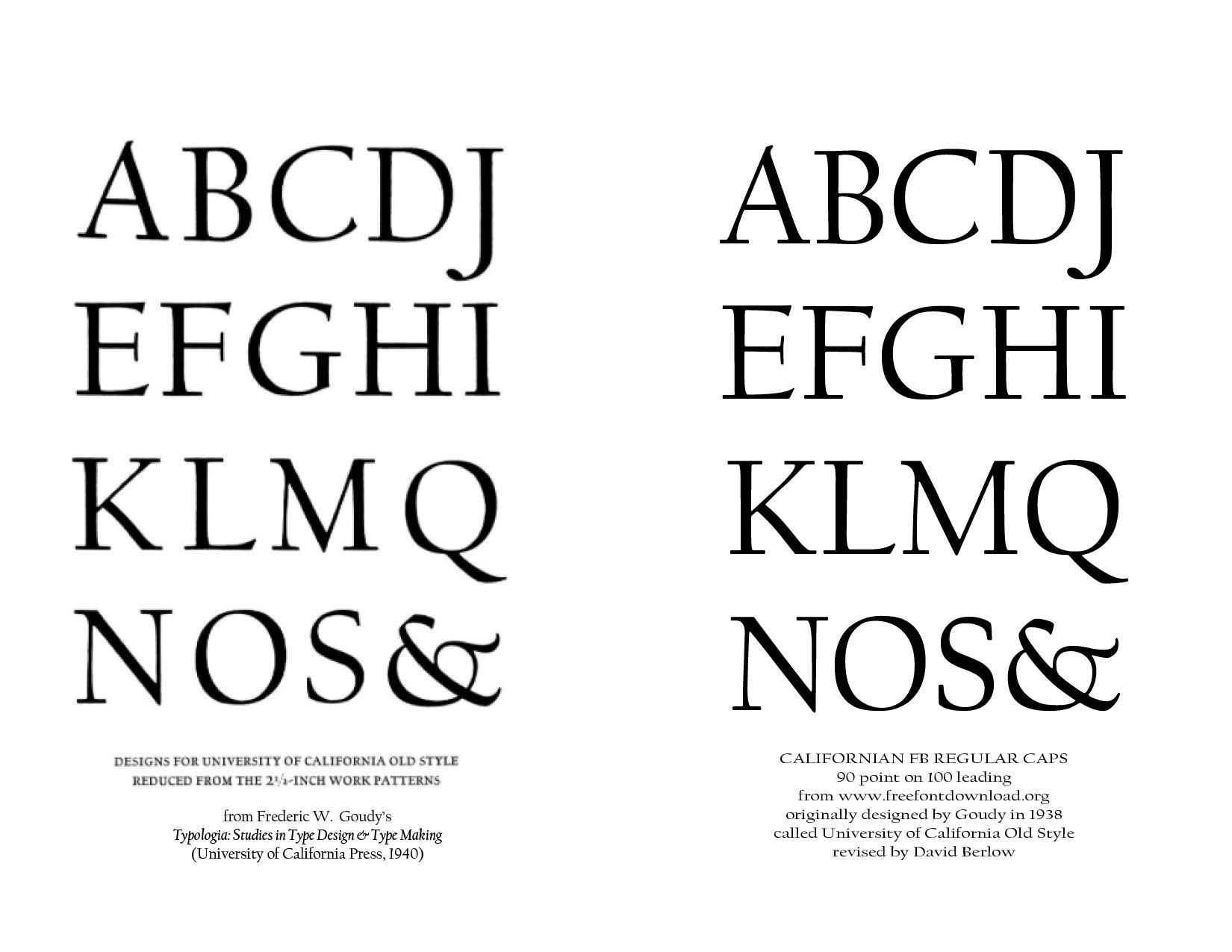

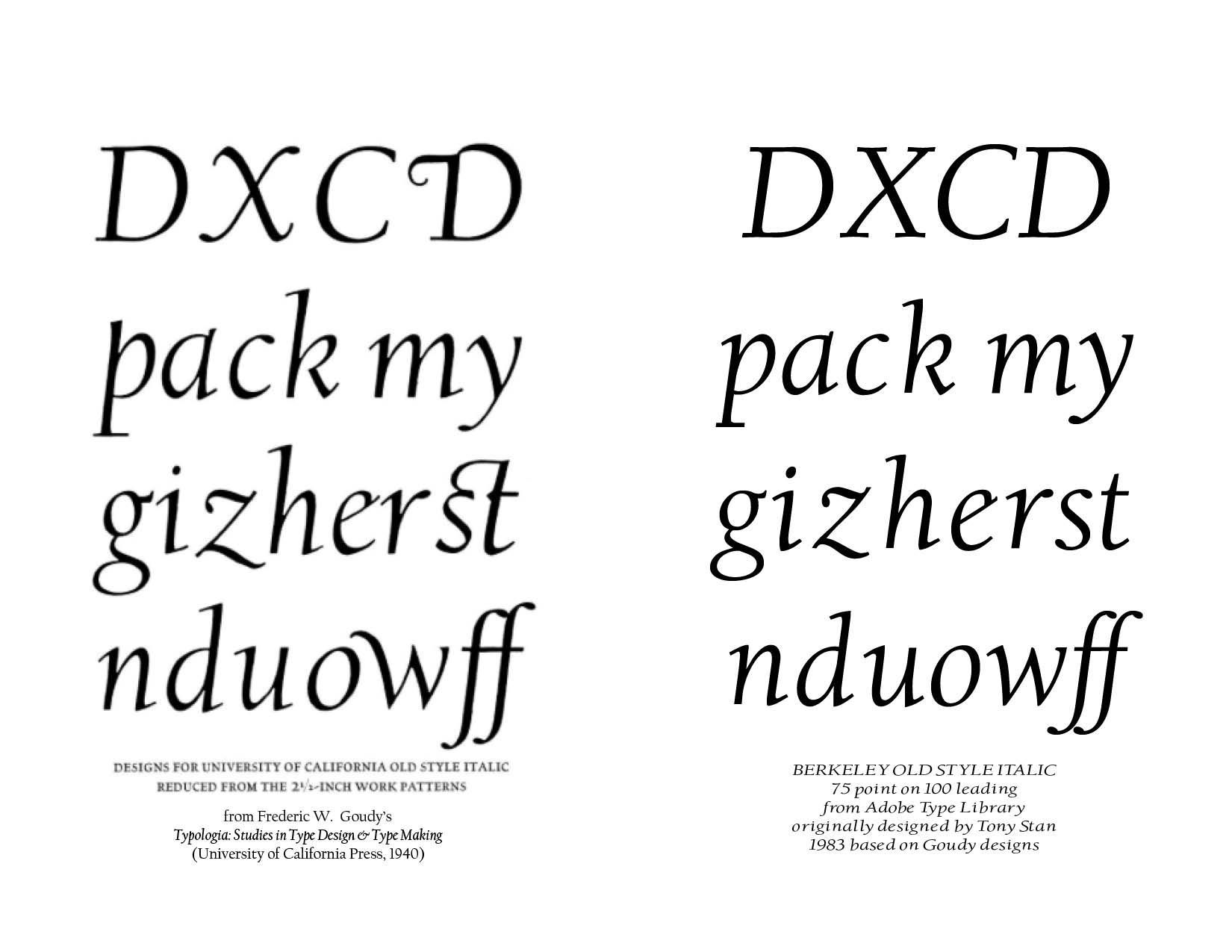

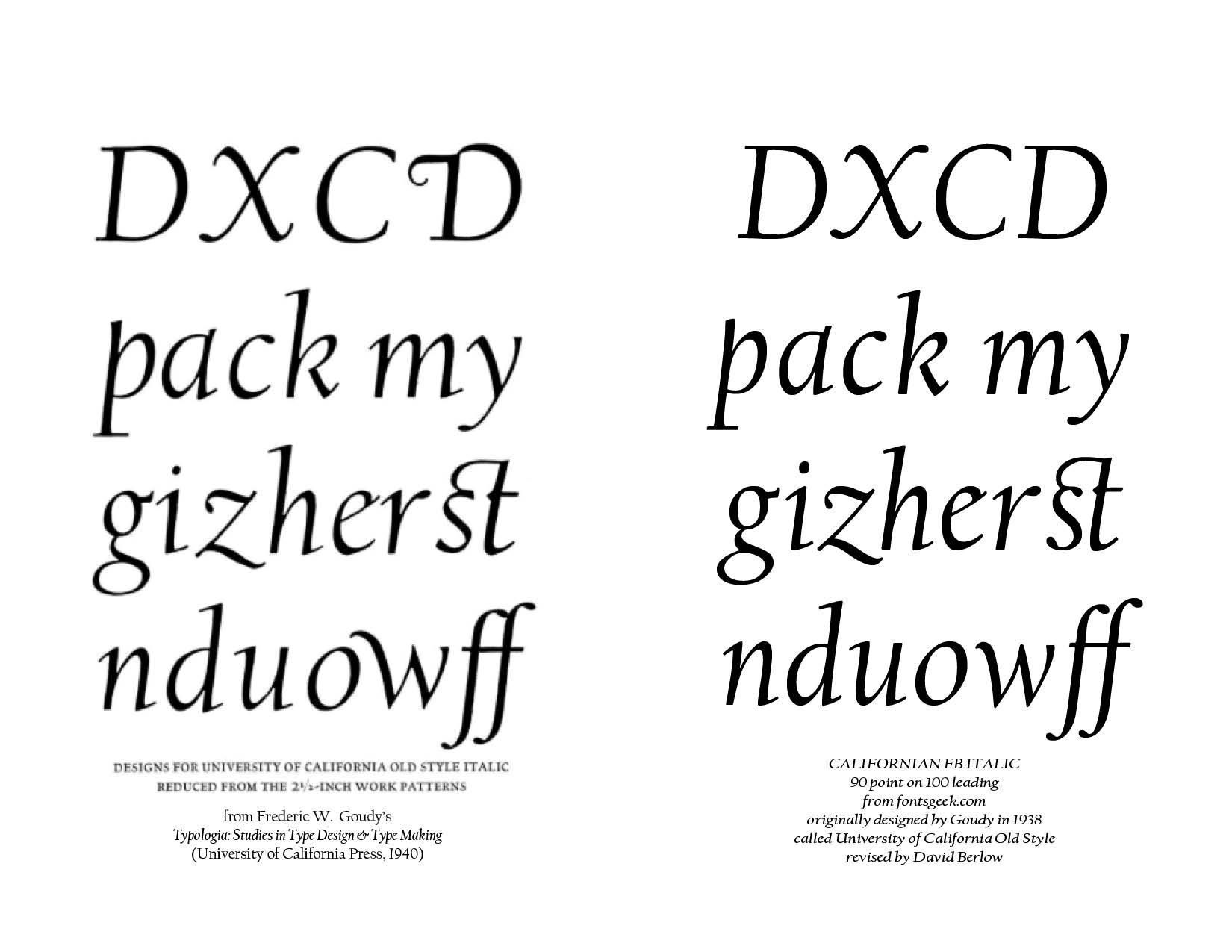

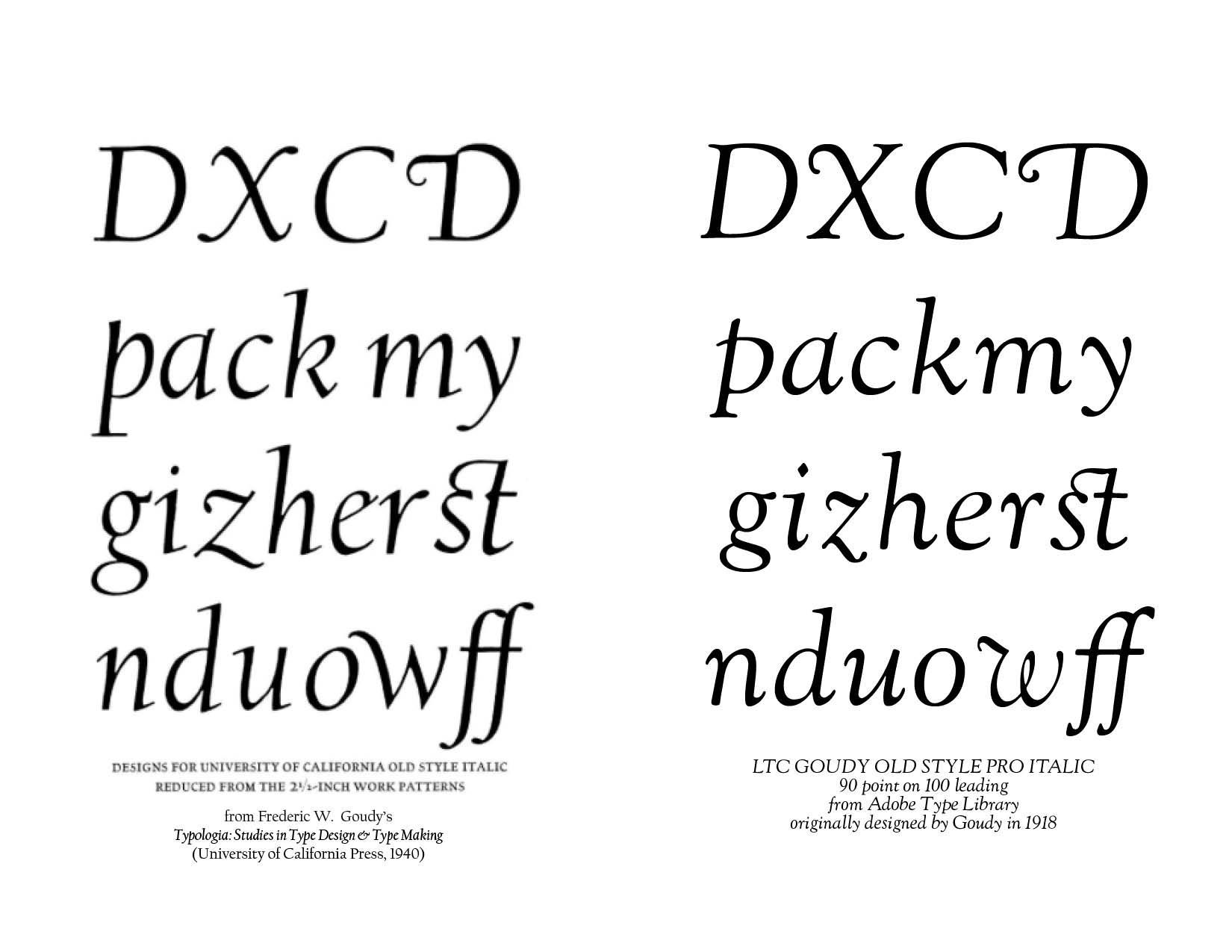

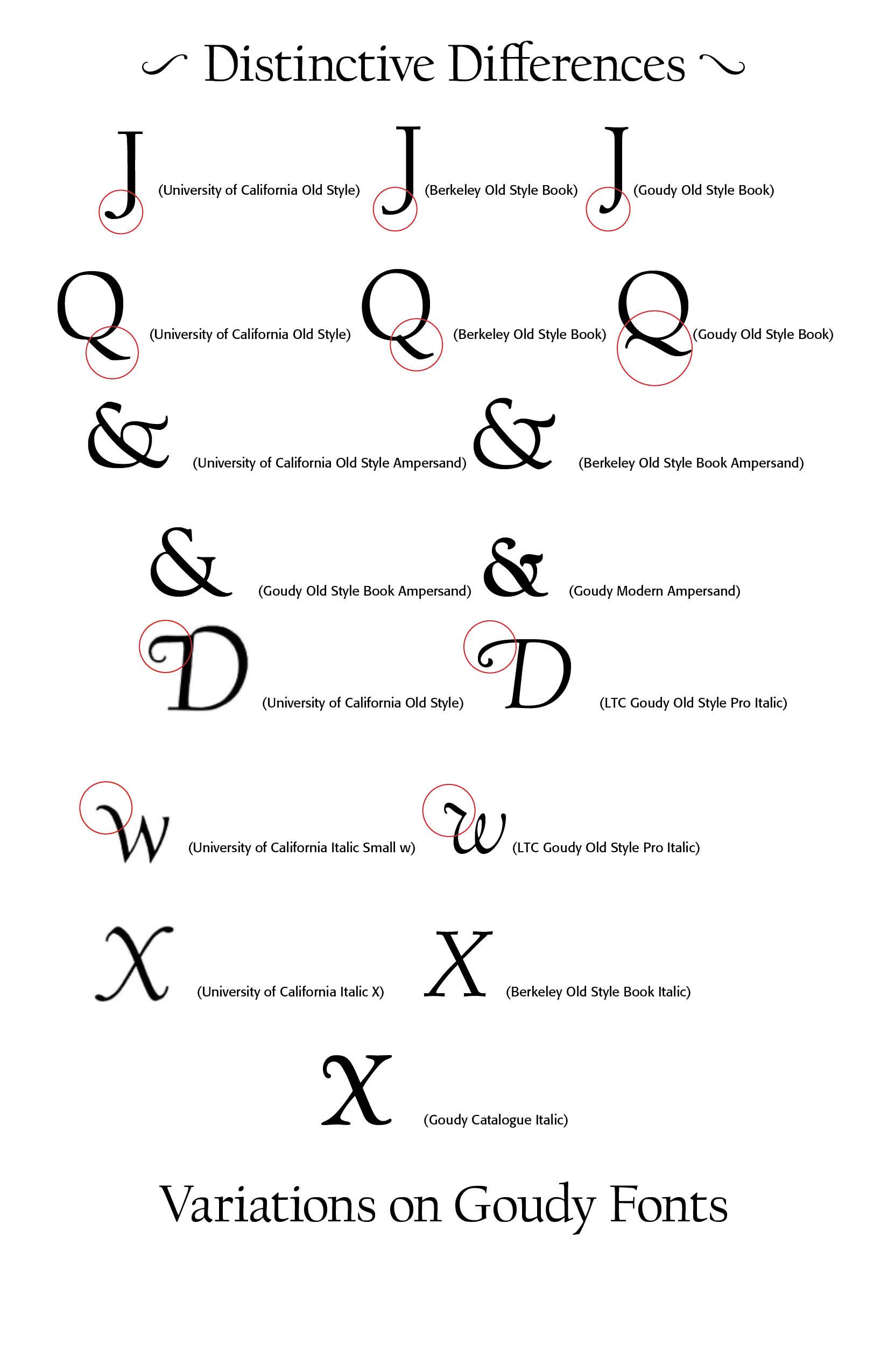

What makes type legible and beautiful? "Legibility depends on there things: first, simplicity, that is, a form having no unnecessary parts [not the bastard simplicity of form which is mere crudity of outline]; second, contrast, as shown by marked differences in the weight of the lines composing the individual letters [stems and hairlines], and also as shown in the varying widths of different letters; and third, proportion, each part of a letter having its proper value and relation to the other parts and to other letters—these three things in connection with the aspects of purpose and use." (130) The University of California at Berkeley hired Goudy to design a typeface for them that radiated legibility and beauty, and Goudy carefully crafted the University of California Old Style Regular and Italic. "He described it as particularly intended to be attractive in mass and said that the italic was intended to be "a refined letter, yet not, I hope, one which may be called prudish…some letters are a bit exuberant. As an italic is [mostly used] to emphasize a word…or sometimes merely to give a lighter touch, I have allowed myself to incorporate here and there in my font some forms more or less fanciful." It was finished just before a fire that destroyed Goudy's workshop, engraving machine and plan drawings, and Goudy noted in his book that it was lucky that he had posted off finished work to Monotype to use as a basis for making punches for their hot metal typesetting system, allowing some letters to be redrawn from patterns." (wikipedia) MyFonts.com notes that "in 1958, Lanston Monotype issued it as Californian. Carol Twombly digitized the roman 30 years later for the University of California; David Berlow revised it for Font Bureau with italic and small caps; Jane Patterson designed the bold."

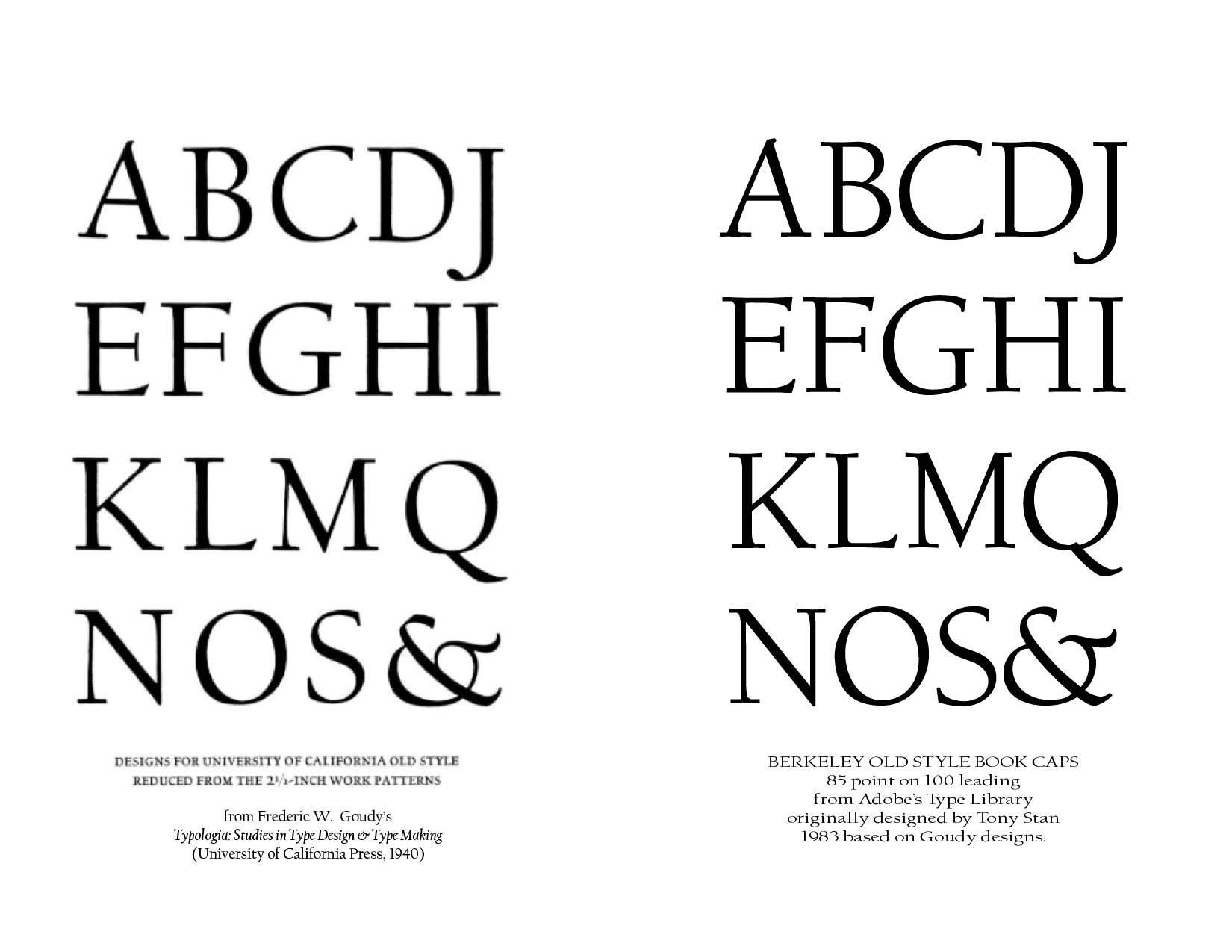

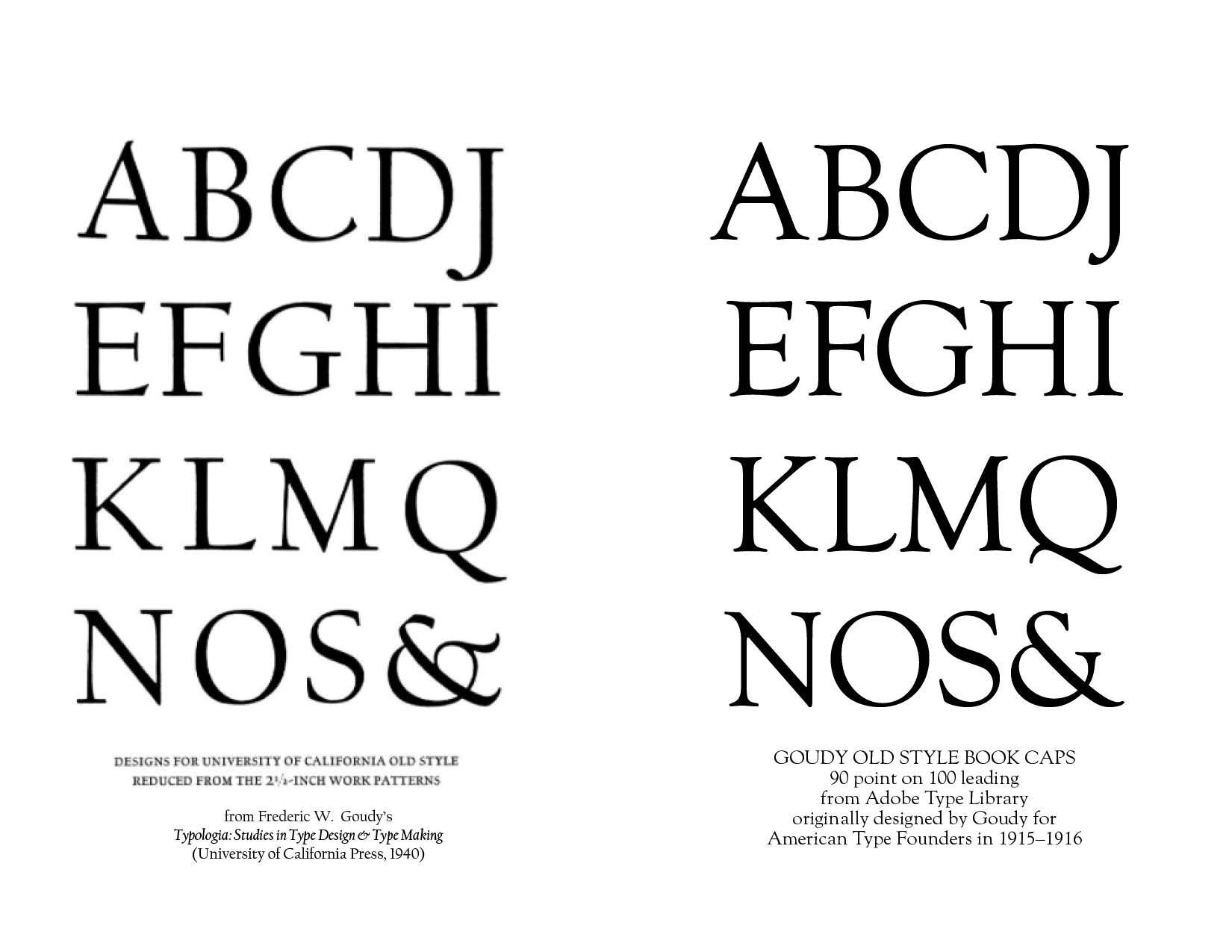

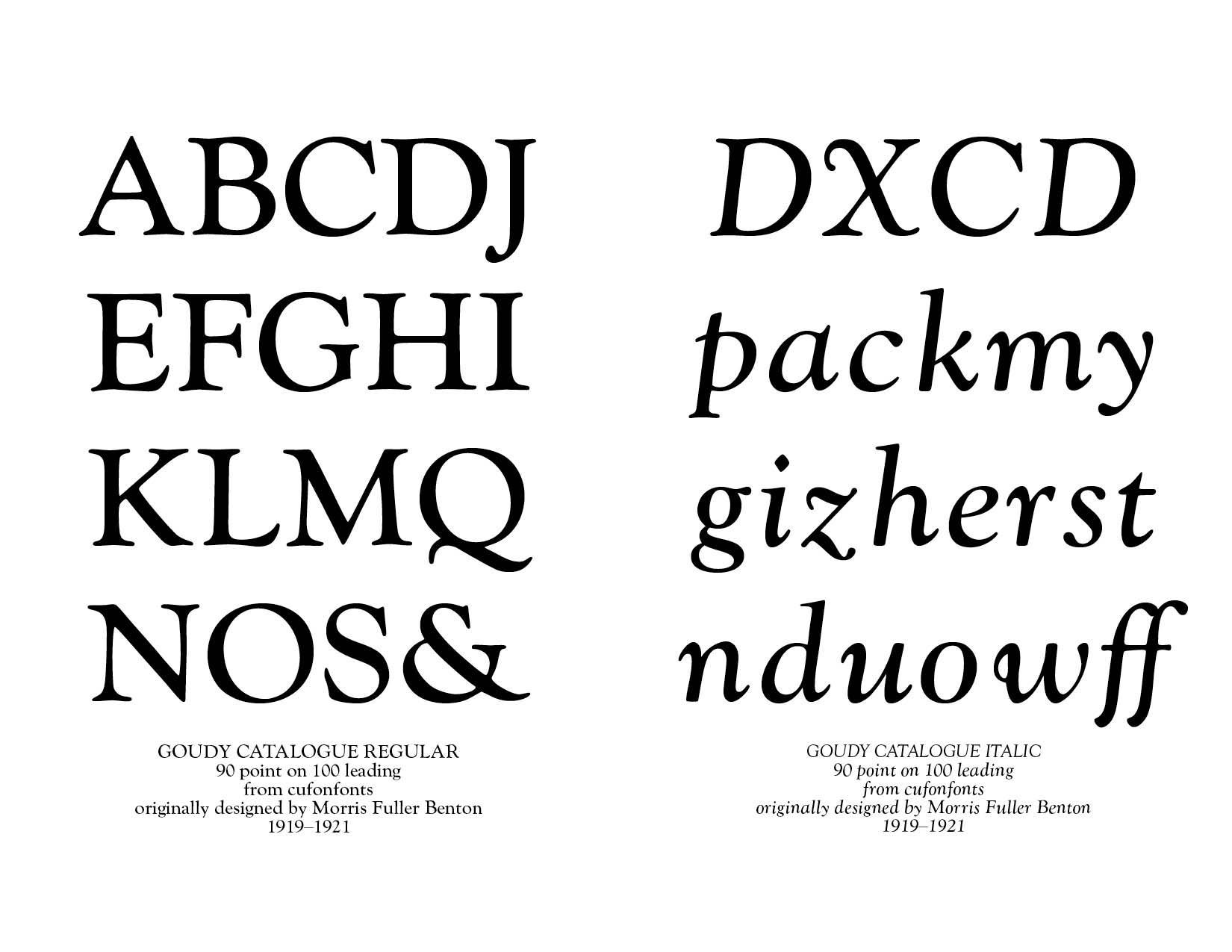

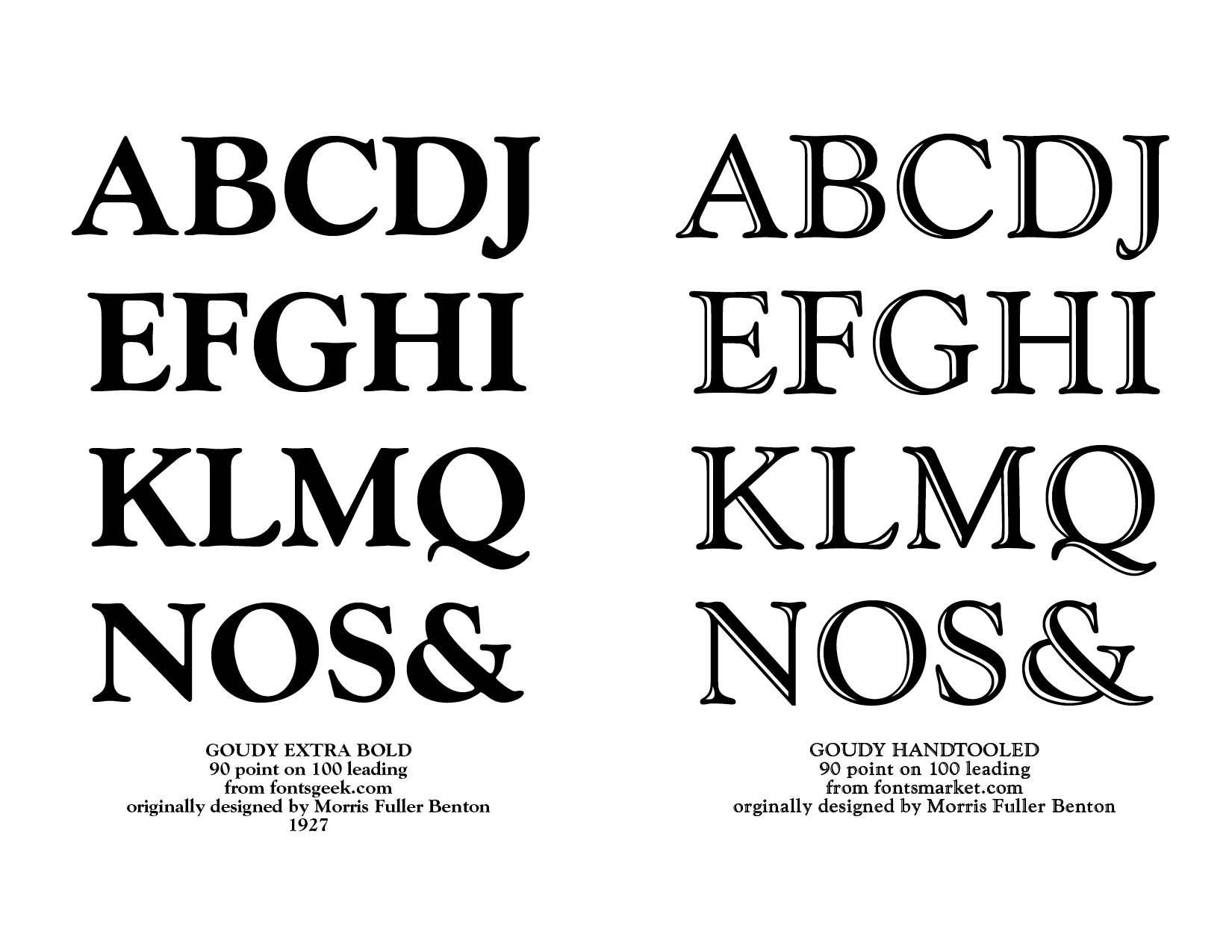

Goudy designed more than 100 typefaces over the course of fifty years. Initially inspired by the cap lettering on a Renaissance painting, Goudy's own individualistic style shows through — the upward pointing ear of the g, the diamond-shaped dots over the I and j, and the roundish upward swelling of the horizontal strokes at the base of the E and L. (See Samples Below) Wikipedia notes that the modern typeface Berkeley Old Style is the digital representation of the University of California Old Style of 1938. There are marked differences, however, as seen in the comparisons below. "Tony Stan redrew the family for ITC (International Typeface Corporation) in 1983, naming it ITC Berkeley Old Style, Berkeley being the city where the University of California Press is located." (from Myfonts.com)

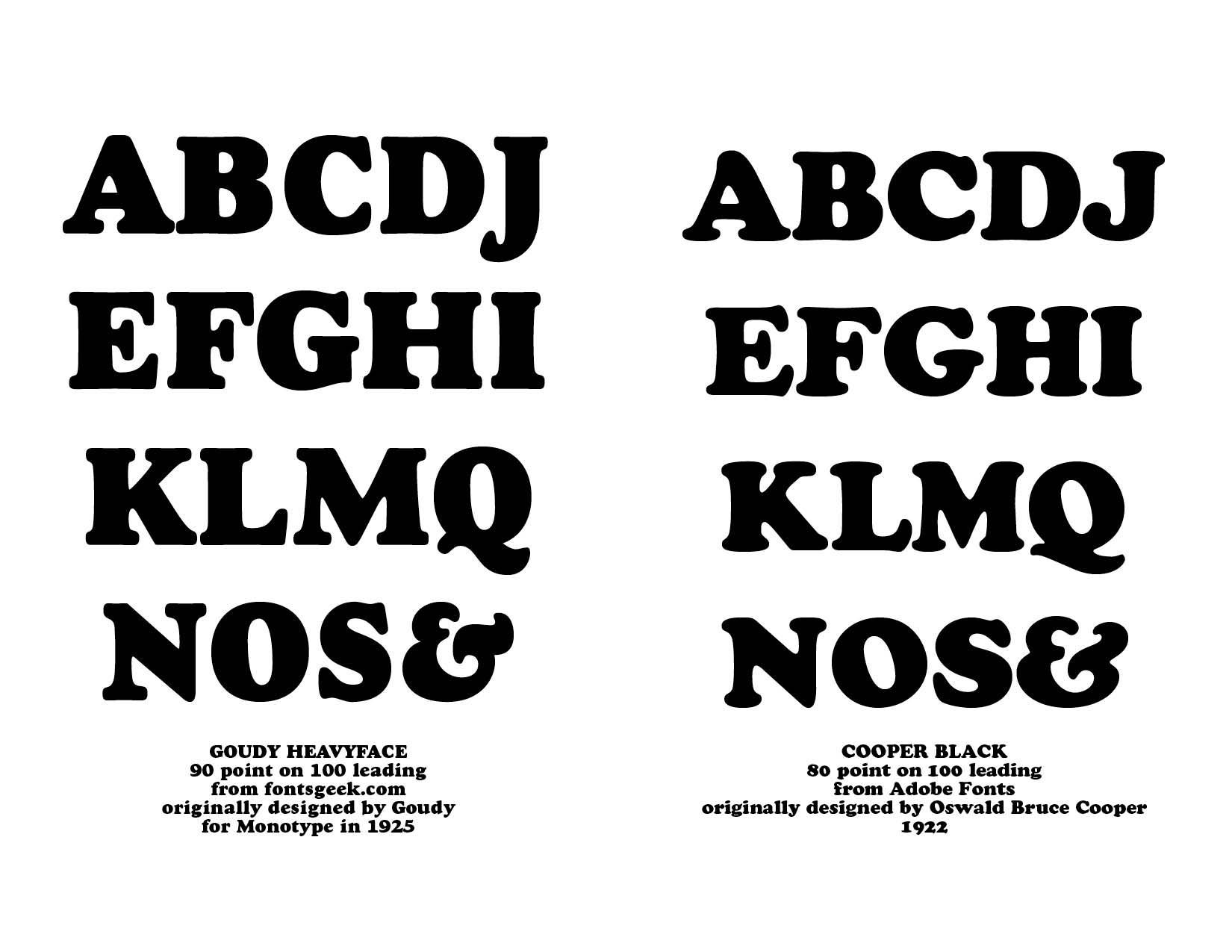

Goudy's type designs continue to show up, especially in display and advertising venues. The included examples below display the beauty and functionality of Goudy's work.

Successful Layout & Design