About Ordinary Type

About Ordinary Type. The type you use everyday is important to your documents. You want legible type that is readable for all kinds of correspondence and reports. We usually give little thought to such type, just trusting our computers to spit out the right look. However, that is often not enough.

Once limited to a few “staples,” users now have thousands of fonts from which to choose. But, who really cares about what typeface is used? You do! Is the type I use “what is pleasing to the eye” (aesthetics/form), or is it simply an issue of “what gets the job done” (mechanics/function)? That’s very often the question.

But, do we care about type? Every time we say, “That’s really nice!” about a wedding invitation, or “This is so clear to read!” about an ad or a flyer, or “That must be really sophisticated!” about a magazine cover, we indicate our care about type. On the other hand, when we squint to read an important announcement, or simply don’t read newspapers or ads due to poor composition, or too many typo’s, we are saying that we care about type. We, consciously or unconsciously, use “bigger” and “bolder” type for signs and directions.

Why? Because we care about legibility. We want the message that our type conveys to get across to those who read it. We want “playful” type for those youth announcements, or children’s functions, or athletic games. While we use either manually paste-in graphics from an art supplier, or computer-generated graphics placed into the text through a page layout program, we show our care about type when we stop to consider what typeface goes with this graphic.

We care about type because we also like to experiment and try a new challenge. So, we spend a few dollars and buy one or two of the many font packs made available to the Mac or Windows user. Then, as many professional typographers quickly point out, we tend to overuse and misuse and do all kinds of “wrong” things with fonts and font combinations. But, we like to experiment with type anyway.

Why should you care about type? Simply because when choosing a typeface, you must consider both character and legibility. Character has to do with the overall personality or mood a typeface projects. Legibility has to do with how easy or difficult it is to recognize each word in a particular typeface. Readability deals with the relative ease with which you can read a printed page. Overall appearance of the page involves how your type is arranged and how the page is designed. Page layout knowledge will help you in the overall “look” of your bulletin or newsletter. Typeface, or font, knowledge will help you better communicate the message you want the reader to receive.

Yes, we want to “get the job done.” We may not want to invest the time or money involved in typographical training. We may not have the slightest inclination to do so. I believe an intelligent and studied use of type choices available to the Macintosh or Windows computer user today can help us achieve that end.

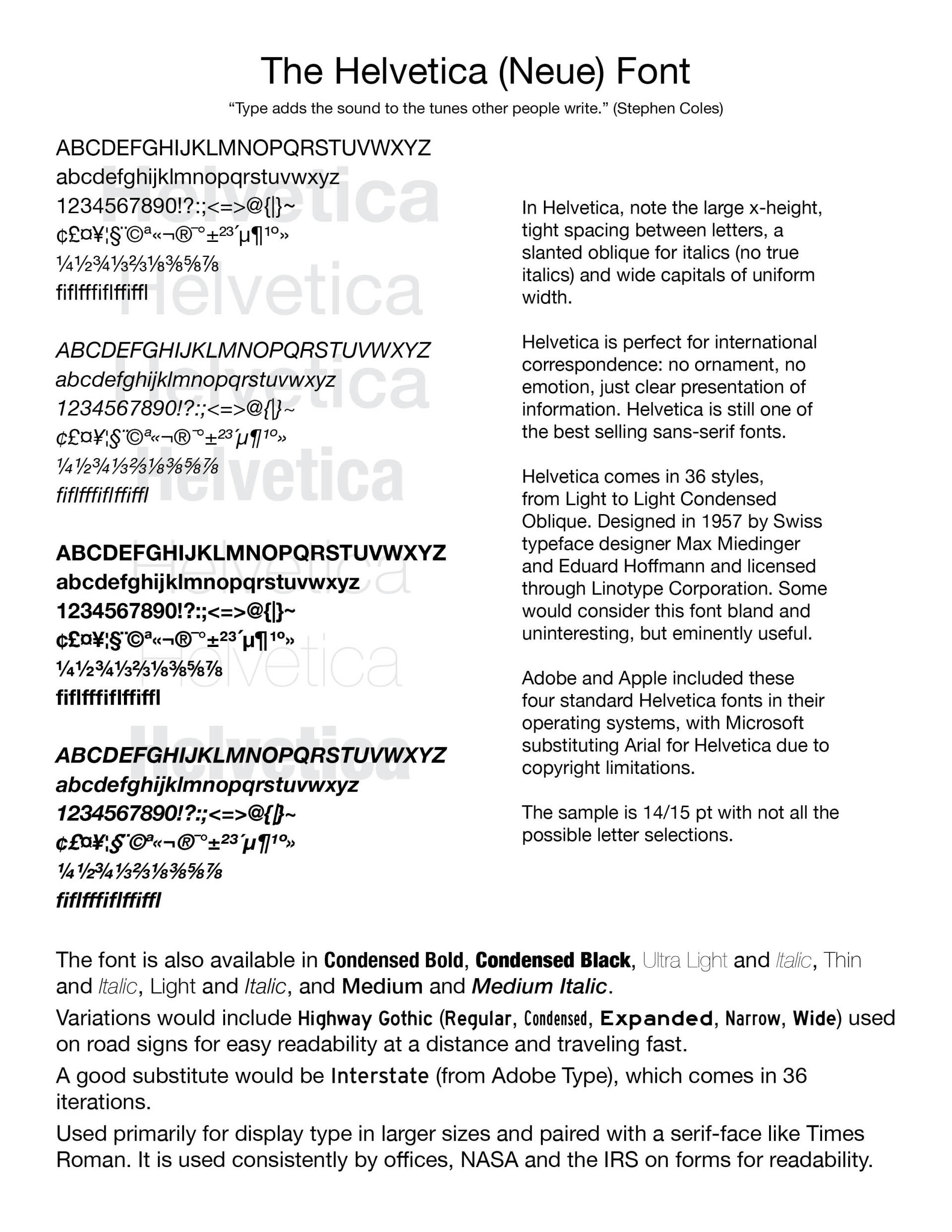

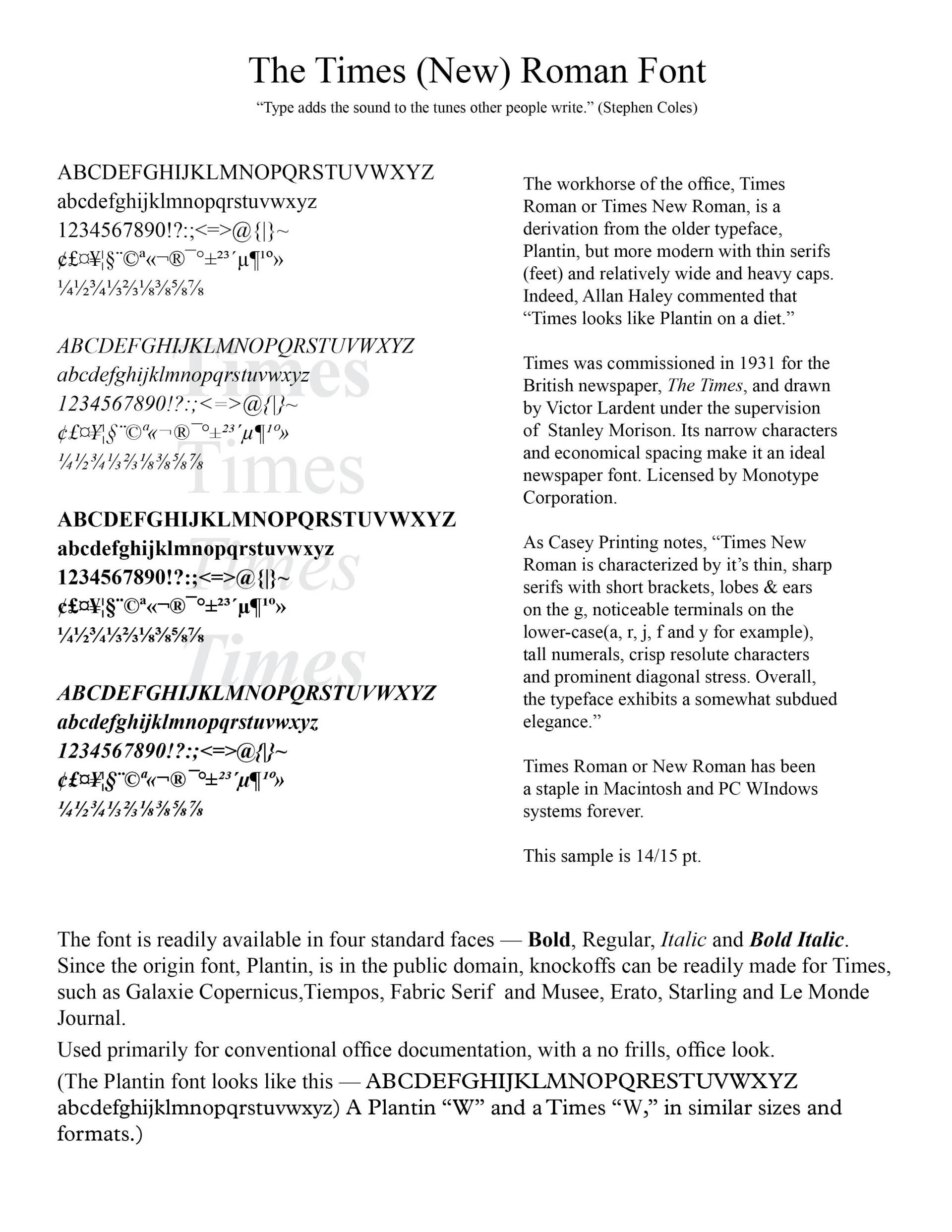

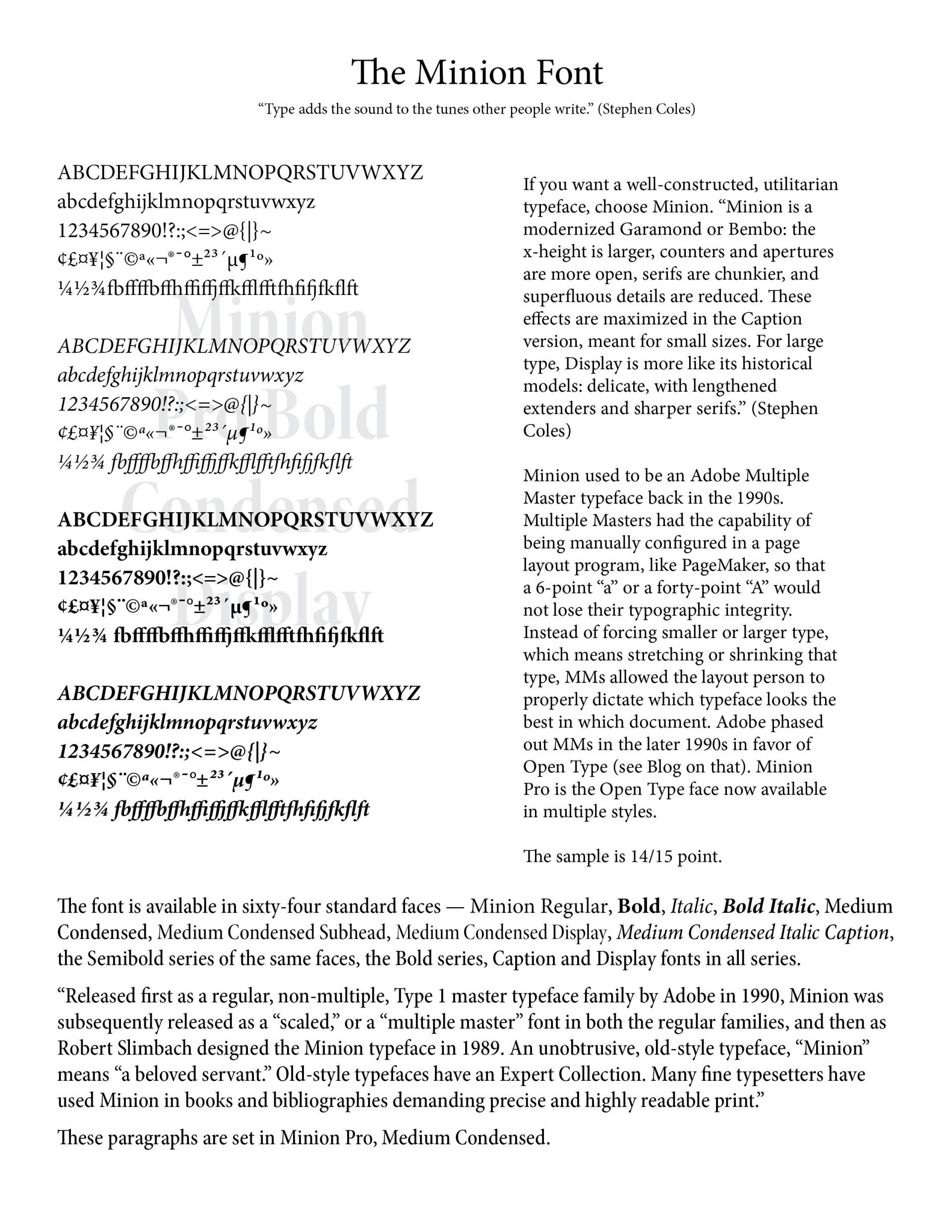

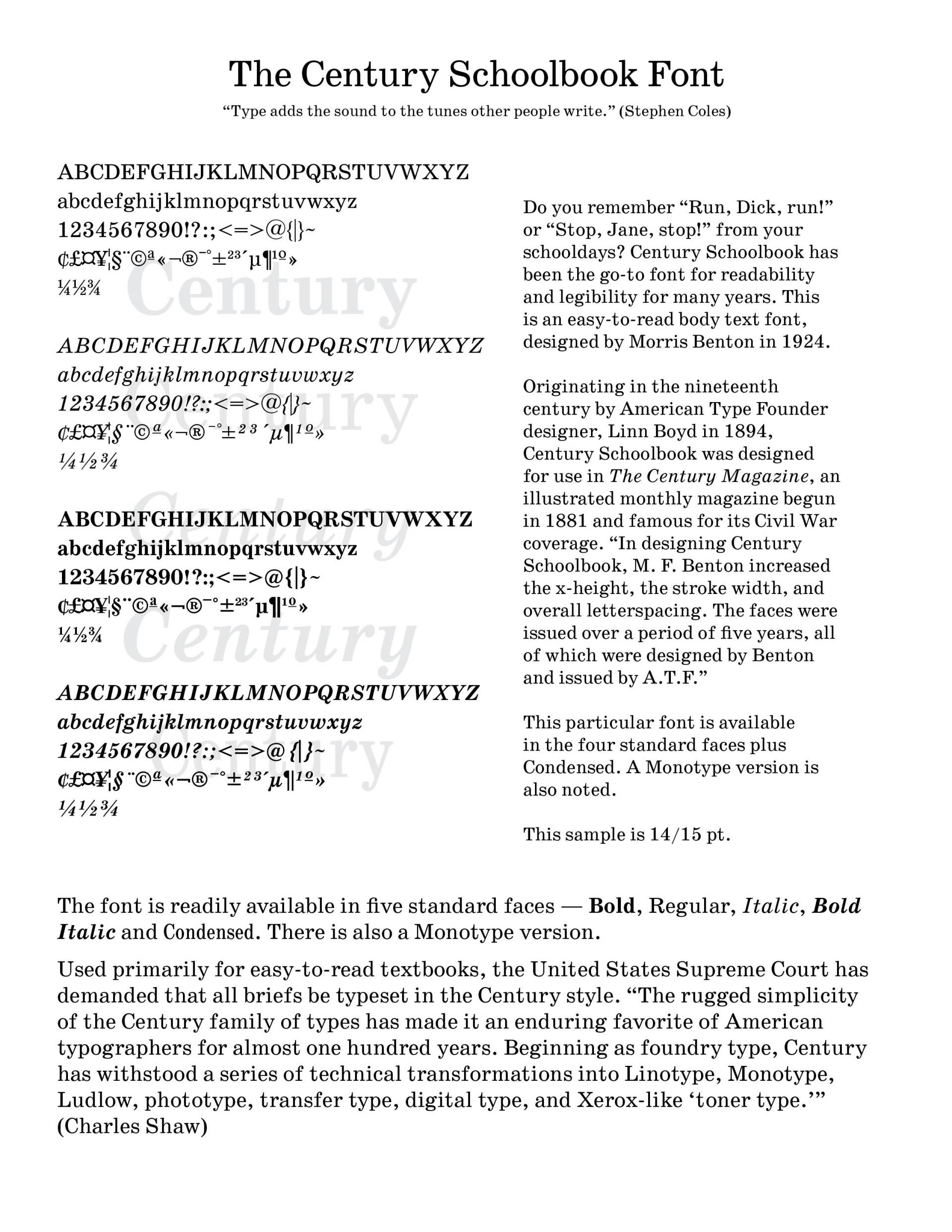

Note the included font sheets below. They will help you understand the type we use everyday and some other type knowledge. I am indebted in these charts to a number of typographers and other articles -- Stephen Coles, The Anatomy of Type: A Graphic Guide to 100 Typefaces, Kindle Edition; Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style (Hartley & Marks, 1992); Philip Brady, Using Type Right: 121 Basic N0-Nonsense Rules for Working With Type (Northlight, 1998); Stephen Moye, Fontographer: Type By Design (MIS Press, 1995); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helvetica; https://www.caseyprinting.com/blog/2013/typography/times-new-roman-the-newspaper-font; Allan Haley (15 September 1992). Typographic Milestones. John Wiley & Sons. p. 106; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plantin_(typeface); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arial)

Successful Layout & Design