What's In A Name?

What's In A Name? Do you remember memorizing your ABCs with the "Alphabet Song" — "ABCDEFG / HIJKLMNOP / QRSTUV / WXYZ / Now I said my ABCs / What do you think of me?/" Our entire life has been framed by the alphabet. For those of us in the typography or typesetting business, the alphabet is our bread-and-butter. Those of us who design fonts and tweak layouts and redesign business logos are, may I say, in love with the alphabet and all that it conveys. But even if you are only slightly interested in history and the alphabet, have you ever wondered where your name came from? Not your surname, which you can find on sites such as ancestry.com, but your NAME, that which people casually call you. My name is "Carl," and I have wondered where those letters came from in the history of letter forms and cultural associations.

Alphabet History The Alphabet is old. Very old. John Coleman Darnell, an Egyptologist from Yale University, in the 1990s made a discovery that rocked the alphabetic world. Looking for Egyptian relics, he discovered two ancient inscriptions at Wadi El-hol in central Egypt, about 30 miles northwest of ancient Thebes. This ancient road had evidence of inscriptions on the walls of the cliffs lining the roadway. The writings show the alphabet's invention from around 2000 B.C. A fascinating study of his report is found in David Sacks, Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet From A to Z.

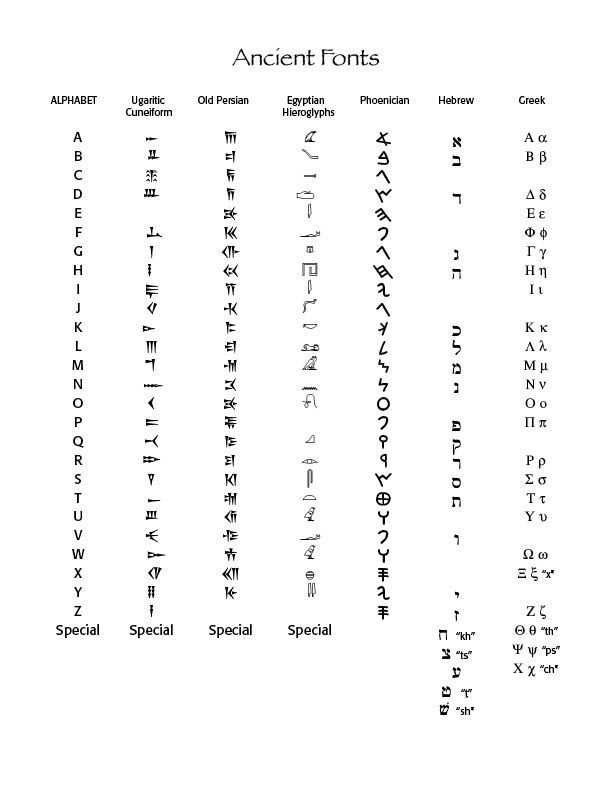

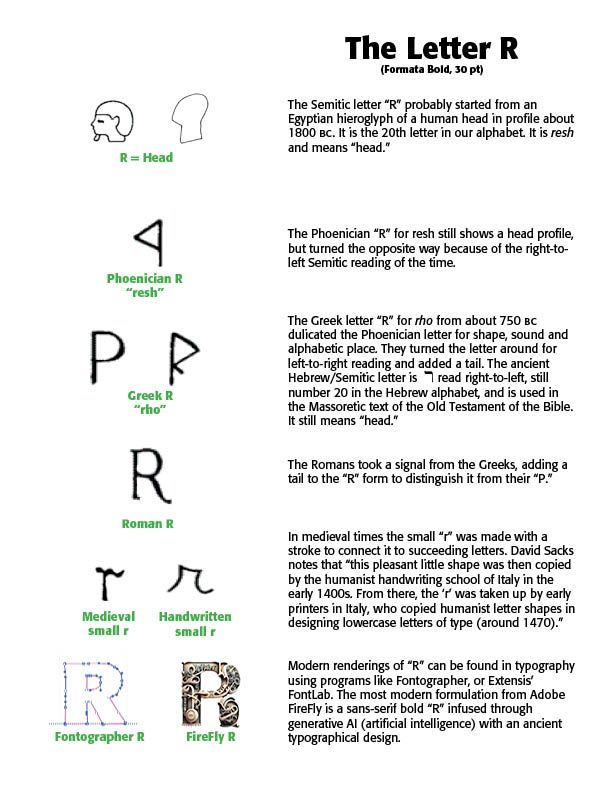

The Egyptians wrote in hieroglyphics (called "sacred carvings"), using pictograms for letters. Pictures of familiar objects were used to convey sounds and words. The ancient Semites borrowed from these pictograms, so that, for example, the picture of a "head" was called resh, and since the word began with the sound of an "r," they selected that image for the sound. Thus, "R" is the sketch of a head.

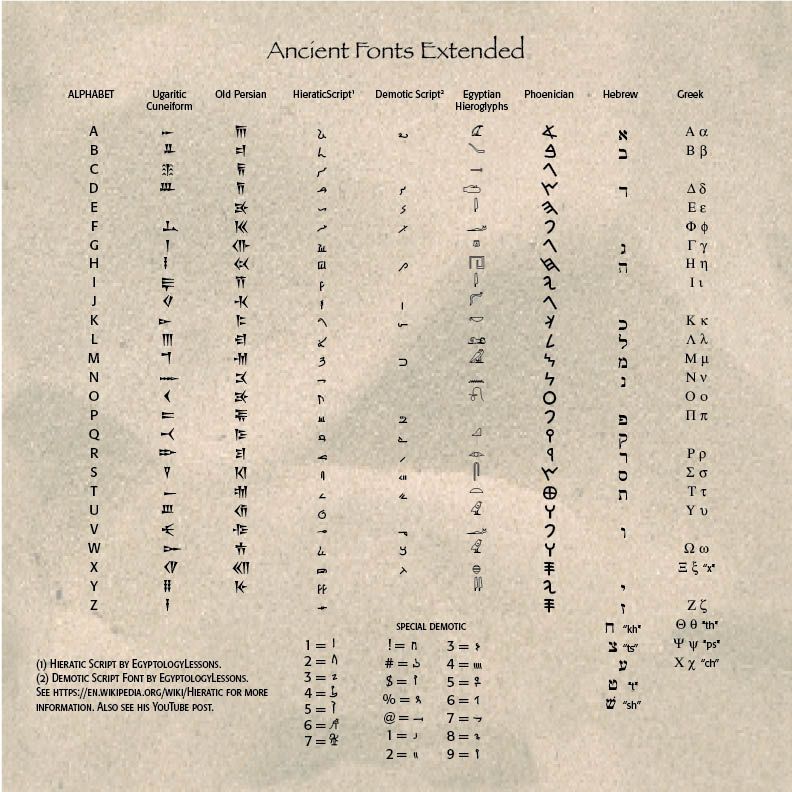

From these backgrounds, the Phoenicians, descendants of people who lived in ancient Canaan, began writing their language in a 22-letter alphabet, sometime before 1000 B.C. They had inherited these letters from other tribes before them, but had the skill and knowledge to formally write them down. By 900 B.C. the Jews and other Near Eastern peoples copied the letters for their own use. The Greeks then followed about 800 B.C., adapting the letters for their own use. The chart on the right shows the Phoenician alphabet and how it relates to our modern alphabet.

Beyond the Phoenicians — The Phoenician alphabet begat the Greek which begat the Etruscan, a people who lived in northern Italy. From there, the Roman alphabet and writing were developed. The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, while the Greek alphabet had 26. Interestingly, the Hebrews, another Semitic tribe which populated the Canaanite region under the influence of Joshua's campaign (in the Bible), only khet (j), qof (q), resh (r) and shin (v) resemble their Phoenician counterparts. The Hebrew writing from right-to-left derives from the Phoenicians.

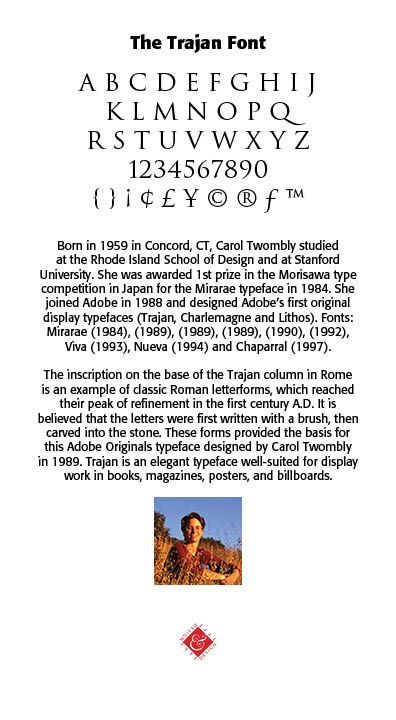

Modern letter forms have their immediate heritage in Roman inscriptions from around 50–120 A.D. The digital version called Trajan, created by Carol Twombly in 1989 for Adobe, reveals some of these Latin forms. In the sixth through tenth centuries, lower case letters (called minuscules) were formed, with modern lettering evolving from the Carolingian scripts. The Emperor Charlemagne used these letters as an educational standard. The Charlemagne font, created by Carol Twombly again, can be seen in the Latin lettering in the sample above. Italics then came into being in the form of cursive script developed in Rome and Florence.

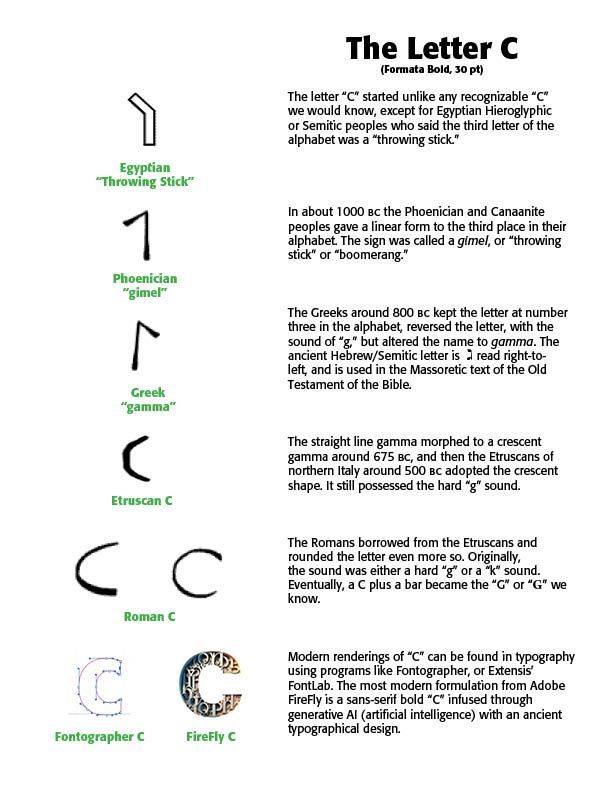

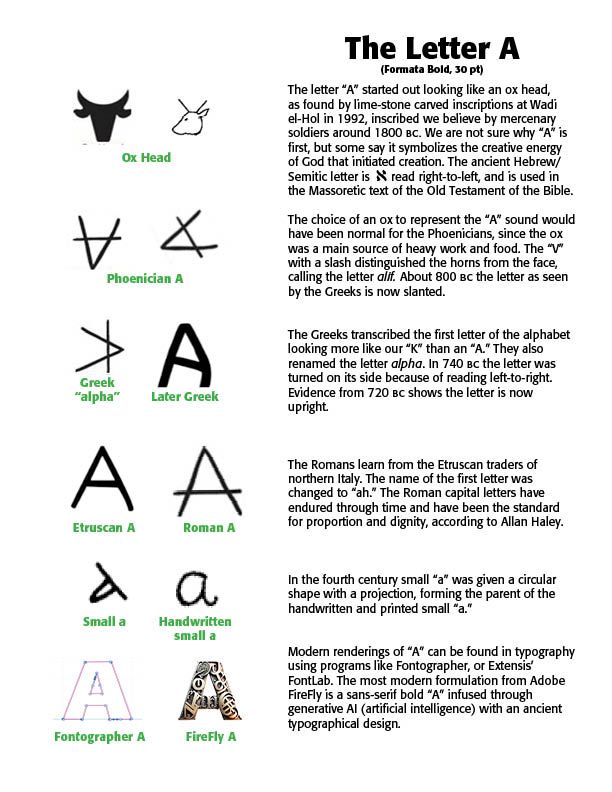

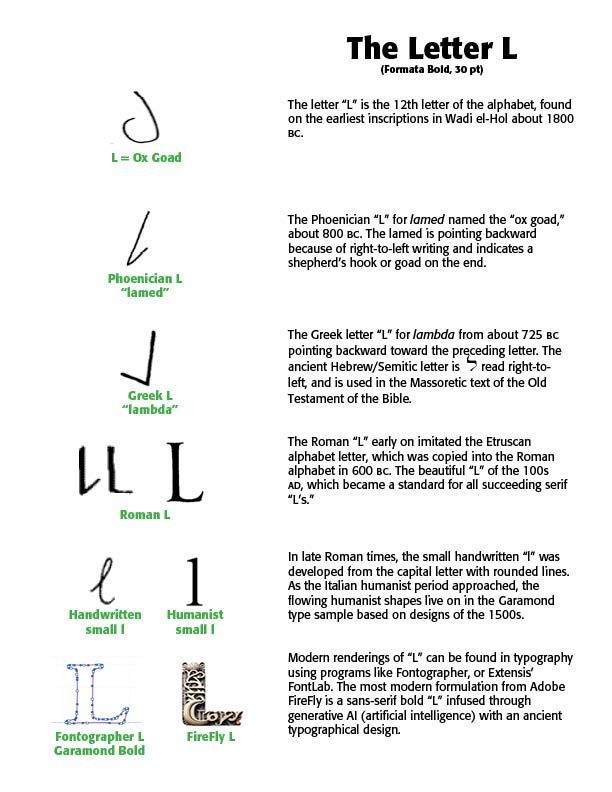

Researching My Name — So, with all this information, and more, I investigated the letterforms that make up my name, CARL. The examples below show that tracing. If you would like more information on tracing your own name, buy a copy of David Sacks, Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet from A to Z, available at Amazon.com.

Successful Layout & Design