Why We Need More Than A Spell Checker

Why we need more than a spellchecker. Spell checkers are great. They help us in busy offices doing busy tasks everyday. EXCEPT they cannot correct errors of statement or errors of typography. Grant Weisbrot of New York City has noted that "it is impossible to efficiently proofread without a knowledge of typesetting and printing procedures." ("The Typographic Eye: Proofreading," Electronic Publishing, May 13, 1994) He gives some examples of errors of statements — spelling when letters are missing, like "he" for "the;" spelling in a piece published in Britain, like "color" for "colour;" using a correctly spelled word in a wrong way, like 20 carat gold (carat is a diamond weight, karat is an alloy of gold, caret is an insertion mark, and carrot is a vegetable); awkward sentence structure, incorrect or inconsistent capitalization; and errors of fact, like the kangaroos of Tibet.

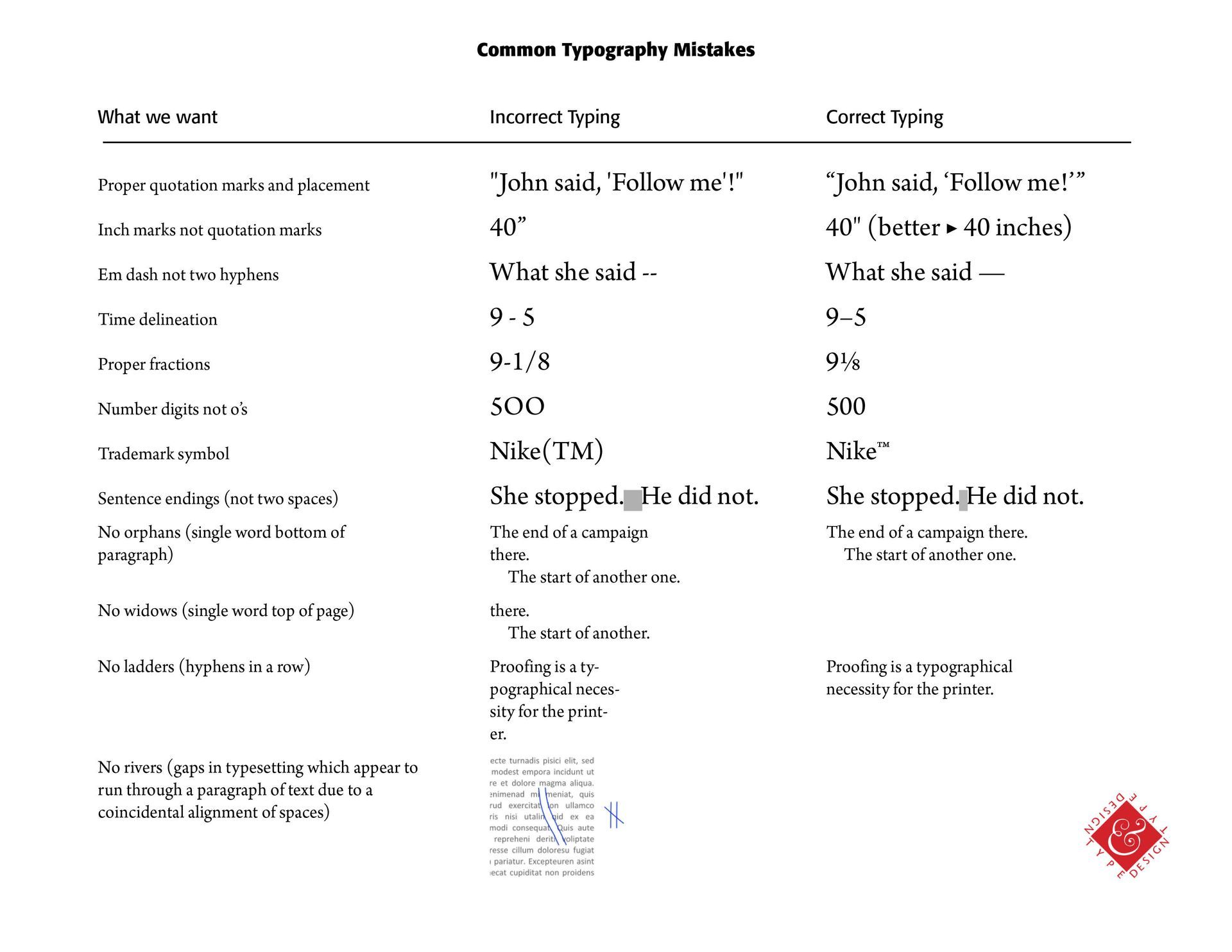

Then there are errors of typography, like primes (' ") for apostrophes or quotes (See Below), or quotes used for inch marks, double-hyphens (--) for an em-dash (—), fractional mistakes (See my Blog on Fractions), kerning that is on or off, word spacing that is inconsistent, unbalanced centered copy, allowing widows, orphans, ladders or rivers (See Below), wrong sized bullets, subscript or superscript failures (NIKE (TM) instead of NIKE™), two spaces after a sentence ending instead of just one space (a common typist mistake), asterisks to represent bullets, using the letter "l" for the number 1, capital O for the digit 0, and misnumbered pages.

Interestingly, the ancient Koreans were known for the quality of their proofreading work. If a novice made one typo, they lost a finger. The second typo caused the loss of a hand! In 1539, France required printers to hire proofreaders or to be fined and held liable for damages due to typographical errors. Today, we just add a "not responsible for typographical errors" to ordinary newspapers and mailers. We have grown sloppy, uncaring, and typographically ignorant—sad to say. Frank Romano in a March 1993 Electronic Publishing article, "The History of the Typo," says that "today artificial intelligence and fuzzy logic are being used to electronically generate typographical errors without human involvement."

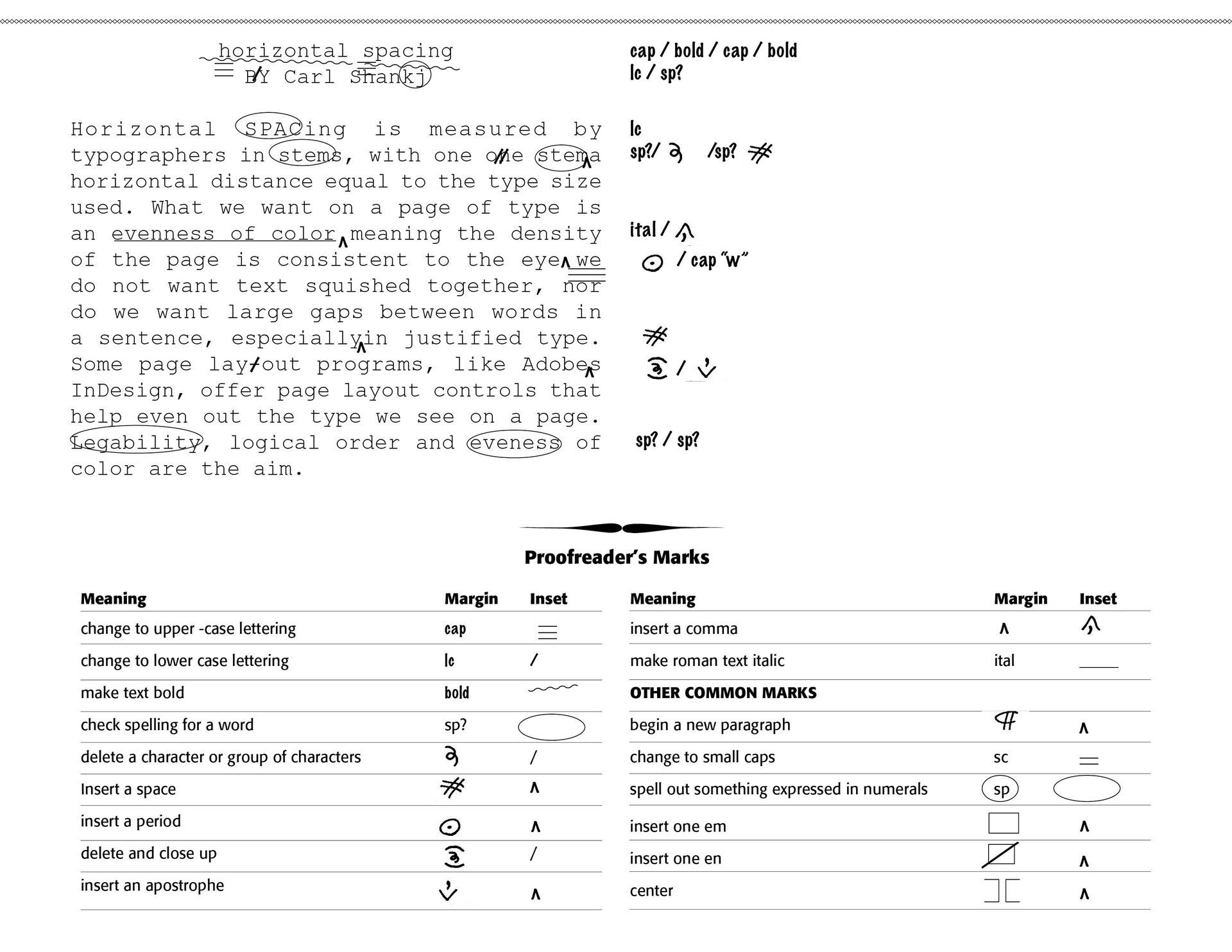

Weisbrot notes that "a proofreader must correct the proof and enhance the typography without ever making changes in the text or specifications; editors usually frown on a proofreader's pretensions to improve the language, but it is rare for a designer to complain if the layout is typographically improved." I have included a Sample below of a typical proofreader's remarks on a submission.

In saying all of this, I read a letter submitted to the Typographical Journal of 1894 of the desperate conditions of a friend of a newspaper comp. She notes — "I do believe that the morning newspaper, set by weary, sweating, half-blinded, nerve exhausted humans, who are driven to the saloon to recuperate by temporary exhilaration, and to early graves by soul and body enervating toil in unwholesome, ill-ventilated, stinking, over-heated composing rooms, a greater curse to humanity than the much dreaded machine [the coming Linotype machine] can ever be. May the morning newspaper set by human hands soon die, I say." (Alexander Lawson, Thoughts on the Typo Workplace, Electronic Publishing, January 7, 1994) We have come a long way from those days, but I wonder what we have given up for speed and so-called efficiency.

Successful Layout & Design